Unlocking the Symbolic World of Crimean Neanderthals

A new study suggests that Neanderthals in the Crimean region crafted and used red and yellow pigments in a way that goes beyond mere survival. Researchers argue that these early humans employed sharpened pigment tools to create precise, symbolic drawings, offering a glimpse into their cognitive abilities and cultural practices.

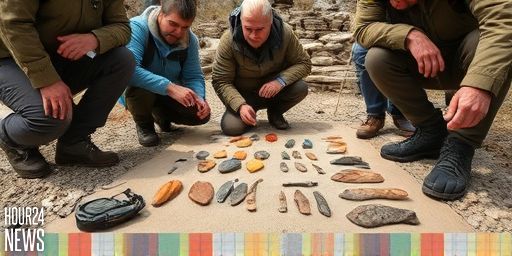

The findings challenge the long-held view that symbolic behavior was exclusive to modern humans. By examining pigment residues, tool marks, and the micro-wear on the edges of pigment implements, scientists reconstruct how Neanderthals produced vivid lines and shapes on soft substrates such as clay, bone, and possibly soft rock. The pigments, derived from naturally red and yellow minerals, appear to have been carefully refined into edge-pointed “crayons” that could be drawn with surprising precision.

The Craft of Edge Sharpening

Central to the new interpretation is the technique used to sharpen the pigment edges. The researchers describe a deliberate, multi-step process: selecting mineral sources, grinding to a fine powder, and then shaping the instrument’s tip to a sharp, controlled point. This sharp edge would enable narrow lines, dotting, and linear drawings that were consistent with symbolic representation rather than crude surface scratching.

The study suggests that Neanderthals experimented with different sharpening angles and edge textures to achieve varying line qualities. Some tools produced fine, delicate strokes similar to sketches, while others yielded bolder marks suitable for larger motifs. The ability to modulate line thickness indicates planning and an understanding of how different marks convey distinct meanings or messages.

Why Red and Yellow?

Red and yellow minerals frequently appear in Upper Paleolithic and Middle to Late Stone Age art across Europe. In Crimea, the presence of these pigments next to habitation sites supports a ritual or communicative purpose beyond utilitarian tasks like hide or tool processing. The pigments could have symbolized status, group identity, or seasonal cycles, inviting speculation about the breadth of Neanderthal symbolic life.

Interactions with the Environment

The Crimean landscape provided access to diverse pigment sources. If Neanderthals actively selected pigment types for their color and stability, this would reflect sophisticated material knowledge and decision-making. The study emphasizes that pigment preparation and application were not incidental; they required planning, resource management, and perhaps social learning—hallmarks of complex cultures.

Beyond the physical tools, the act of drawing itself implies a sensory and cognitive engagement with the world. Creating images—whether geometric shapes, signs, or representational motifs—could have served as communication, storytelling, or social bonding within Neanderthal groups.

Broader Implications for Neanderthal Cognition

These archaeological clues contribute to a growing body of evidence that Neanderthals possessed a sophisticated behavioral repertoire. The creation of symbolic art, the use of color, and the refinement of drawing instruments suggest a level of abstract thinking and cultural transmission previously attributed mainly to Homo sapiens. While the exact meanings of the drawings remain speculative, the capacity to plan, execute, and reuse artistic techniques demonstrates a cognitive flexibility that reshapes how we view these ancient neighbors.

Conclusion

The Crimean discovery adds to a nuanced narrative about Neanderthal life. Red and yellow pigment “crayons” sharpened into points reveal a symbolic dimension to their material culture, underscoring a shared human tendency to communicate and express through art. As researchers refine dating methods and broaden site comparisons, we may glimpse an even richer picture of Neanderthal creativity that challenges stereotypes and invites a reassessment of how symbolic behavior emerged across early humans.