Lead Exposure: A Long-Shadowed Force in Human Evolution

Lead is often cast as a modern toxin, with its health threats tied to industry and urban life. Yet a striking new study suggests that lead exposure may have haunted our ancestors for nearly two million years and, in surprising ways, might have given Homo sapiens an edge over Neanderthals. The findings add a provocative piece to the complex puzzle of how our species diverged and why language and brain development differ between ancient populations.

What the researchers looked at

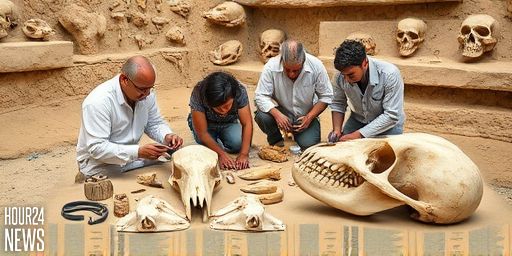

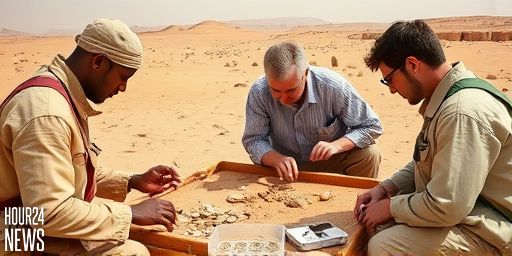

An international team examined the lead content in 51 fossilized hominid teeth, dating from 100,000 to 1.8 million years old. The samples encompassed a diverse set of relatives: Homo sapiens, Neanderthals, and several early Homo species, along with more distant relatives such as Australopithecus, Paranthropus, Gigantopithecus, and fossil orangutans and baboons. The goal was to trace patterns of lead exposure across different lineages and time periods to see how pervasive this toxin-like presence might have been in prehistory.

Uncovering episodic exposure across lineages

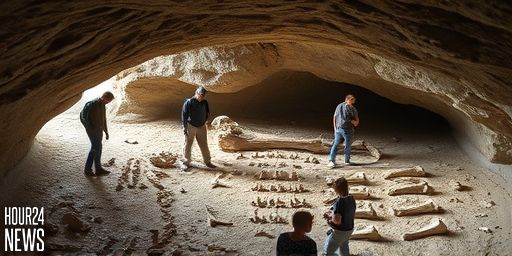

The team reported clear signals of episodic lead exposure in about 73 percent of the specimens, with Australopithecus, Paranthropus, and Homo lines showing exposure in roughly 71 percent of their samples. These findings imply that lead, likely from natural environmental sources such as volcanic activity, wildfires, and geologic processes, permeated the diets of ancient hominids in varied and seasonally dependent ways. This challenges the long-held assumption that lead exposure was primarily a consequence of industrial-era activities.

Different exposure patterns among species

Within the set, patterns varied. Paranthropus robustus teeth showed consistently low-level lead lines, suggesting sporadic, perhaps acute exposure—potentially linked to events like forest fires. In contrast, Australopithecus africanus and Homo species exhibited more frequent, higher lead concentrations, which could reflect more varied or bioaccumulative diets in those populations. These nuanced differences hint at how environmental pressures and feeding strategies interacted with each species’ biology.

A possible genetic and neurological edge for Homo sapiens

Beyond the dental measurements, the study explored a striking biological thread: the NOVA1 gene. Lab-grown brain organoids were created with two variants of NOVA1—one found in modern humans and another in Neanderthals and other extinct species. The ancient variant disrupted a crucial brain gene, FOXP2, which encodes a protein essential for speech and language development. Brain organoids with the modern NOVA1 variant showed less disruption, suggesting a potential protective effect against lead’s neurological harm.

Developmental biologist Alysson Muotri of the University of California, San Diego, described this as an extraordinary example of how environmental pressures—here, lead toxicity—could drive genetic changes that bolster survival and language capabilities. The researchers caution that this is not a definitive proof that lead gave humans a linguistic advantage, but it offers a compelling mechanism for how environmental stressors might shape cognitive evolution.

Implications for health and history

Lead toxicity is linked to a spectrum of modern health issues, from neurological disorders to cardiovascular problems. Historically, these effects are often tied to heavy industrial activity. But the ancient record suggests that even natural sources of lead could influence brain development and behavior in significant, detectable ways. If modern humans had a protective NOVA1 variant, it could be one of many genetic factors that helped Homo sapiens weather environmental challenges and develop complex language—an essential tool for cooperation and cultural transmission.

The bigger picture

While this study does not prove that lead exposure directly caused Homo sapiens to outpace Neanderthals, it opens a provocative line of inquiry. The interaction between environmental exposure and genetic evolution could account, at least in part, for some differences in brain development and communicative ability between ancient populations. As researchers continue to scrutinize the fossil record and simulate ancient environments, we may uncover more examples of how a heavy metal’s whisper influenced the arc of human history.

Bottom line

The story of lead in our evolution is intertwined with climate, geology, diet, and DNA. The idea that lead exposure might have conferred a selective advantage—and possibly contributed to language development—adds a fascinating wrinkle to our understanding of human origins. It reminds us that evolution is often a story of unlikely pressures and remarkable genetic responses, unfolding over millions of years.