Lead Exposure: A Surprising Thread in Human Evolution

Lead is commonly painted as a modern toxin, but a provocative new study suggests the metal has haunted humanity for nearly 2 million years. More striking still, episodic exposure to lead might have given Homo sapiens an evolutionary nudge over Neanderthals and other early relatives. By examining fossil teeth and comparing genetic-era brain models, researchers are revisiting how environmental pressures could shape long-term survival and even language development.

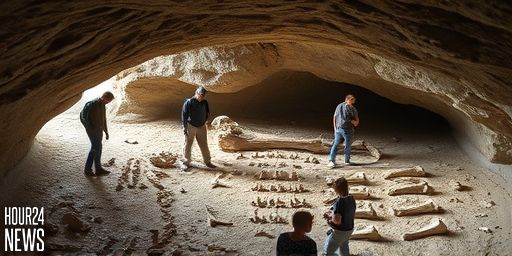

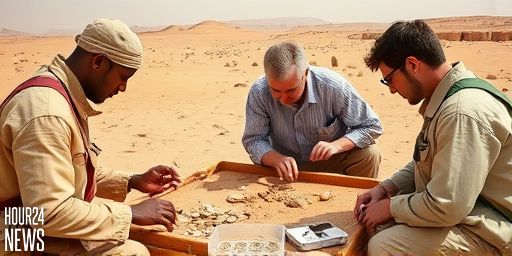

How the Study Traced Ancient Lead Exposure

An international team analyzed 51 fossilized hominid teeth dating from about 100,000 to 1.8 million years old. The sample included Homo sapiens, Neanderthals, and various early Homo species, along with distant relatives such as Australopithecus, Paranthropus, Gigantopithecus, and fossil orangutan and baboon species. Using high-precision methods, the researchers looked for lead lines in enamel to reconstruct periods of exposure over a child’s development and across generations.

Remarkably, the team reported clear signals of episodic lead exposure in roughly 73 percent of the specimens (71 percent within a trio of lineages: Australopithecus, Paranthropus, and Homo). These patterns varied by species, hinting at different dietary and ecological routes of lead intake—whether through water, food, or environmental contamination from natural sources such as volcanic activity or wildfires.

The findings challenge the assumption that lead exposure is exclusively a modern hazard tied to industrial activity. Instead, they raise the possibility that early hominids routinely navigated environments with fluctuating lead levels that could affect neurological development and behavior.

From the Teeth to the Brain: A Genetic Angle

Beyond tracing toxic exposure, the researchers explored how ancient environmental stressors might interact with genetics related to brain development and speech. In lab-grown brain organoids, two variants of the gene NOVA1 were tested: one version common in modern humans and another variant found in Neanderthals and related extinct species. The organoids carrying the ancient NOVA1 variant showed significant disruption in the activity of FOXP2, a gene tied to speech and language development. By contrast, organoids with the modern NOVA1 variant appeared less damaged by lead exposure.

Lead toxicity may, therefore, have created selective pressure favoring genetic changes that helped mitigate neurological harm. As lead exposure fluctuated over generations, lineages carrying the modern NOVA1 variant could have gained a survival advantage through more robust communication abilities and better cognitive resilience.

What This Could Mean for Our Evolutionary Narrative

The study does not claim a direct causal link between lead exposure and the emergence of modern human language. Instead, it presents a compelling scenario in which environmental toxins could drive genetic adaptation and neural development. Researchers emphasize that modern lead exposure levels are a different problem entirely, with well-documented learning disabilities, cardiovascular disease, and other health risks. Still, the research highlights an intriguing dynamic: natural sources of lead may have intermittently shaped brain development across millions of years.

Lead’s reach in human history isn’t limited to ancient teeth. The metal’s broader tale includes how it might intersect with cognition, behavior, and social communication. If modern humans carry a unique NOVA1 variant that better tolerates lead’s neurological blows, this could be one piece of a multifaceted puzzle explaining why our species persisted and evolved complexity where Neanderthals—despite their many strengths—faced different constraints.

Limits and Implications

While the results are provocative, the authors caution that the study doesn’t prove lead exposure directly caused an evolutionary edge. The interpretation rests on indirect evidence from dental chemistry and laboratory models. More research is needed to map precise exposure timelines and to determine how widespread protective genetic variants were across ancient populations. Nevertheless, the work contributes to a broader understanding of how environmental pressures can steer genetic and cognitive trajectories over deep time.

Why It Matters Today

The narrative that humans benefited from adversity in the deep past offers a lens for examining how current environmental toxins could influence development. It underscores the importance of studying historical exposures to grasp modern health risks and the ways our genomes respond to chronic stressors. In a world where lead exposure remains a public health concern in some regions, the study also invites reflection on the long arc of human resilience and the intricate interplay between environment and evolution.

Bottom Line

Lead exposure in ancient times likely varied across species, environments, and diets. The possibility that such exposure spurred genetic adaptations—potentially influencing language-related brain networks—adds a novel layer to the story of human evolution. It’s a reminder that our journey from early hominids to modern humans is not just about traits we observe today but also about hidden pressures that may have sculpted our biology in subtle, lasting ways.