The 43-Year Chronicle of Number 16

In the remote scrublands of Western Australia, a trapdoor spider earned an unlikely distinction: Number 16, a Gauis villosus, lived to an impressive 43 years, becoming the longest-living spider ever recorded. Her life, chronicled in a long-term study published in Pacific Conservation Biology, offers rare windows into the habits of mygalomorph spiders, their ecological roles, and the delicate balance of the Australian bush. Number 16’s story is not merely a curiosity; it’s a case study in longevity, habitat stability, and the vulnerabilities that persist even for the most enduring organisms.

The Lifespan That Defied Expectations

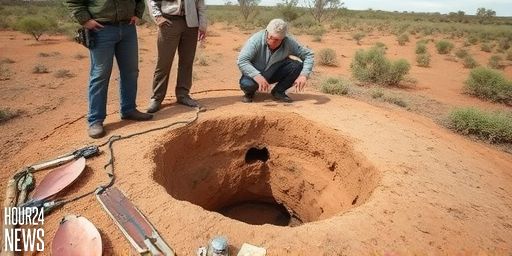

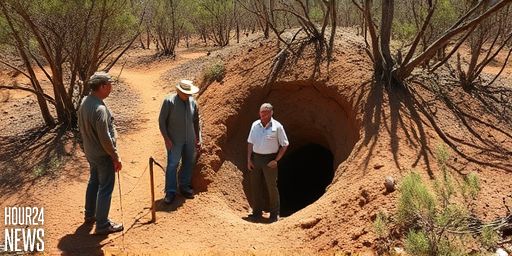

The spider’s journey began in 1974 as part of a long-running project led by Barbara York Main at the North Bungulla Reserve near Tammin, South-Western Australia. The study sought to understand population dynamics and behavior in trapdoor spiders, a group known for their sedentary lifestyles and cryptic burrows. Unlike many spiders that have shorter life expectancies, Number 16 thrived in her undisturbed native bushland, a habitat that provided consistent conditions and limited energy expenditure.

Leanda Mason, a biologist at the University’s School of Molecular and Life Sciences, emphasizes that Number 16’s extraordinary longevity was tied to her species’ life-history traits. The trapdoor spider’s habit of remaining within the same burrow for life reduces the energy costs associated with hunting and dispersal, allowing a more extended, more stable life in favorable microhabitats.

Why This Spider Survived So Long

Several factors converged to support Number 16’s 43-year tenure. First, her sedentary lifestyle minimized exposure to predators and environmental fluctuations. Second, her metabolism was remarkably low, conserving resources over decades. Third, the burrow system she inhabited offered protection from heat, drought, and predation, acting as a stable health reservoir that buffered her from many of the ecological stressors that shorten the lives of more mobile species.

These traits, observed through Barbara York Main’s meticulous records and subsequent analyses, help scientists understand not only the biology of Gauis villosus but also the broader dynamics of trapdoor spiders within Western Australia’s ecosystems.

The End of an Era: A Parasitic Wasps’ Toll

Number 16’s life came to a close in 2016, not from age but from a parasitic encounter. Researchers reported that the lid of the oldest spider’s burrow had been pierced by a parasitic wasp. The eggs of these wasps develop inside the host, and their larvae eventually kill the spider from within. It was a poignant reminder that even the most enduring species are vulnerable to natural ecological interactions. A six-month gap between observations only underscored the fragility of the oldest matriarch in a world governed by predation and parasitism.

As the Pacific Conservation Biology study noted, the death of Number 16 at the age of 43 marks an extraordinary but not invincible life history. Her legacy now informs how scientists interpret longevity, life-history strategies, and conservation concerns for arachnids and their habitats.

Conservation Lessons from Number 16

The life of Number 16 highlights the value of stable, undisturbed habitats for longevity and resilience. Her story underscores a broader conservation message: protecting native bushland ensures that specialized, long-lived species have the space to thrive. In a world facing development pressures and climate change, insights from long-term studies of spiders like Number 16 can guide habitat preservation, monitoring programs, and public understanding of biodiversity.

Beyond zoology, Number 16’s journey invites reflection on how human stewardship can align with natural life histories—promoting sustainability, conserving resources, and appreciating the quiet endurance of creatures that often live out of sight in the world’s most delicate ecosystems.