New clues from a 3,000-year-old workshop

The Iron Age transformed human civilization with durable tools, improved farming, and new forms of conflict. Yet the origin story of how iron became central to technology remains debated. A fresh examination of a 3,000-year-old site in southern Georgia—Kvemo Bolnisi—offers compelling evidence that iron may have entered metallurgical practice not as a separate discovery, but as a byproduct of copper smelting experiments.

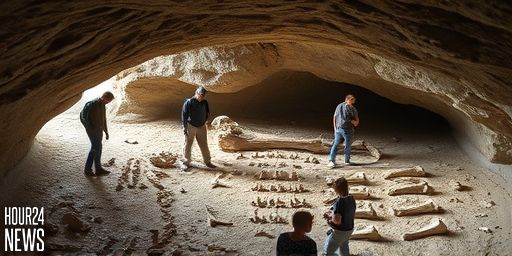

The site revisited: what the researchers looked for

Anthropological archaeologists Nathaniel Erb-Satullo and Bobbi Klymchuk of Cranfield University revisited Kvemo Bolnisi, a workshop once associated with iron production due to virtually abundant hematite and heavy slag waste. Using advanced chemical analysis and high-resolution microscopic imagery, the team questioned whether the iron oxide present at the site acted as a direct ore source or served another purpose within the copper-smelting process.

Iron oxide as flux, not ore

Their findings point to a different function for iron oxide: a flux. In metallurgy, flux substances are added to furnaces to improve smelting conditions, often by facilitating slag formation, refining metal blends, or protecting the melt from impurities. At Kvemo Bolnisi, the iron oxide appears to have enhanced the copper-smelting process rather than supplying iron metal as a standalone ore. This distinction matters because it reframes the site as a laboratory where copper workers inadvertently experimented with iron-related materials, laying the groundwork for later iron production.

Implications for understanding how iron began

Erb-Satullo explains the significance: “It’s evidence of intentional use of iron in the copper smelting process. That shows that these metalworkers understood iron oxide—the geological compounds that would eventually be used as ore for iron smelting—as a separate material and experimented with its properties within the furnace.” The result is a plausible pathway from copper metallurgy to iron metallurgy, driven by curiosity and practical problem-solving in the smelting workshop rather than a sudden, isolated breakthrough.

A broader view of technological transitions

Iron’s rise reshaped farming, warfare, and daily life across continents over roughly 700 years of the Iron Age. While Kvemo Bolnisi offers a tantalizing glimpse into the experimental mindset that could have sparked iron production, researchers are cautious about generalizing from a single site. They compare Kvemo Bolnisi with other contemporaneous sites, including discoveries in Israel, to build a broader picture of how iron might have emerged from copper-processing networks.

Why the site still matters

Iron-bearing minerals often share geologic neighborhoods with copper deposits, increasing the likelihood that early metalworkers repeatedly encountered iron in smelting contexts. The absence of written records and the rust-prone nature of iron have long obscured origins studies. Kvemo Bolnisi, with its slag and hematite interpreted through modern geochemical and materials-science techniques, offers a rare window into the minds of ancient metallurgists as they tested ideas using everyday materials.

The future of metal history research

As analytical technologies advance, scientists can re-examine old sites with fresh questions. Kvemo Bolnisi demonstrates that our understanding of pivotal transitions can shift when modern geology and materials science meet archaeology. Erb-Satullo envisions a continued loop of observation, testing, and reinterpretation: “There’s a beautiful symmetry in this kind of research, in that we can use the techniques of modern geology and materials science to get into the minds of ancient materials scientists.” Slag, once seen as mere waste, becomes a meaningful record of experimentation and progress.

Key takeaway

The Kvemo Bolnisi workshop hints that the Iron Age may have begun with copper-smelting experiments that leveraged iron oxide as flux. If confirmed across multiple sites, this narrative would shift the origin story of iron from a sudden discovery to a disciplined process rooted in experimentation within copper production.