Flat Thumb Nails: The Tiny Tool That Changed Everything

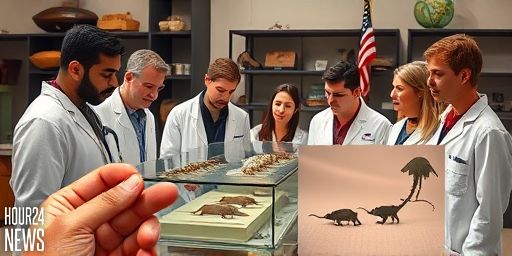

Rodents are the most diverse order of mammals, thriving from deserts to rainforests and cities. A new study based on the Field Museum archives suggests a tiny feature—the flat nail on the thumb—could help explain this global success. By surveying 433 species (out of roughly 522 known worldwide) and cross-referencing museum records with modern image databases, researchers traced how thumb nails align with diet and habitat choices across the group.

A Common Pattern, A Common Tool

Most rodents share a distinctive hand anatomy: one flat nail on the thumb and four curved claws on the other digits. In the study, about 86 percent of the examined species show this pattern, and the researchers found evidence that many of them use their hands to handle food, rather than feeding directly with the mouth. This hands-on approach likely complements their famous ever-growing incisor teeth.

From Nut-Holding Ancestors to Modern Diversity

The team concluded that the earliest rodents carried a flat thumb nail precisely to grasp food—think of a squirrel cradling a nut while gnawing. This grip would have given them a reliable way to handle hard objects, reducing accidental drops and enabling more efficient feeding. Over time, this trait persisted in most descendants, becoming a hallmark of the lineage that diversified into thousands of species living in a wide range of environments.

How the Thumb Nail Works With Rodent Teeth

Rodents are defined by sharp front chisel-like incisors followed by strong grinding teeth behind them. When a rodent bites into a nutshell or seed, the sturdy grip provided by the flat thumb nail allows precise control of the item while the incisors do the cutting. As researchers put it, the arrangement “lets them hold and gnaw with a grip that most other animals lack.”

Variations That Evolved With Lifestyles

Not all rodents retained the classic thumb nail. Some lineages adapted to very different lives. Burrowers such as the spalacids and certain pocket gophers (Geomyidae) reduced or replaced the thumb nail with a better digging claw on the thumb. It’s easier to imagine a sturdy claw scrabbling through soil than a flat nail trying to scratch into hard earth.

Other exceptions exist. The sap-eating, tiny neonate tree-dweller Sciurillus pusillus has a very short thumb with no nail or claw on the digit, so the thumb becomes less important for handling food. Meanwhile, the Caviidae family, which includes capybaras, has largely abandoned the idea of a functional thumb altogether for grazing, an activity similar to sheep grazing rather than nut-holding.

Why a Small Thumb Made a Big Difference

As Feijó and colleagues note, tiny anatomical details can drive big evolutionary outcomes. Nuts are energy-dense; accessing them requires deft manipulation and a secure grip. The thumb nail, by enabling that grip, may have allowed rodents to exploit a resource that was harder for rivals to process. This, in turn, could have reduced competition and opened niches across continents, fueling the extraordinary radiation of rodent species we see today.

Conclusion: A Handful of Nails, a World of Rodents

What began as a simple adaptation on a single digit helped shape one of the planet’s most successful mammal groups. By tracing the history of the flat thumb nail, researchers illuminate how a small feature can ripple through ecology and evolution, leaving a lasting mark on the natural world.