Introduction

A breakthrough in paleoanthropology could rewrite the early chapters of human evolution. A one-million-year-old skull found in Yunxian, China, is being studied with cutting-edge digital reconstruction techniques, challenging the view that our distant ancestors diverged primarily in Africa.

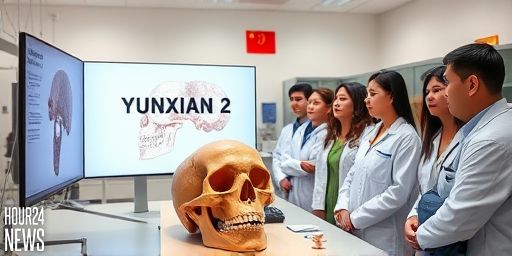

The Yunxian 2 Skull Comes Alive

Discovered in 1990, the crushed Yunxian 2 skull was long assigned to Homo erectus. Researchers employed computed tomography, structured-light imaging and advanced virtual reconstruction to create a complete model of Yunxian 2. They built the digital shape using a similar skull as a template and then compared the model with more than 100 other specimens to identify shared and divergent traits.

A closer look at the brain and traits

Early analyses point to features such as a brain size larger than previously thought for this region, a finding that aligns Yunxian 2 with lineages like Homo longi or even Homo sapiens, suggesting an earlier diversification than once assumed.

Implications for Human Evolution

As Chris Stringer of the Natural History Museum in London notes, “This changes a lot.” If these interpretations hold, a million years ago our ancestors may already have split into distinct groups, painting a more intricate and multi-regional picture of early human evolution.

Columnist Michael Petraglia of the Griffith University Australian Centre for Human Evolution later noted that the results “cloud the waters,” underscoring the possibility that East Asia played a more central role in hominid evolution than previously recognized.

Rethinking Asia’s Role

The Yunxian 2 study adds to a wave of new discoveries that place East Asia at the heart of human origins. It sits alongside groundbreaking updates like Homo longi, recognized as a distinct lineage in 2021, illustrating how modern imaging and comparative analysis are reshaping when and where our ancestors arose.

Methodology and Evidence

To build the Yunxian 2 reconstruction, the research team combined high-resolution CT scans, structured-light imaging and sophisticated virtual modeling. A second, similar skull served as a template to inform the model, which was then compared with more than a hundred fossils to map shared and contrasting traits.

Broader Context and Future Work

Scholars caution that findings of this kind require replication and broader sampling. If validated, they could imply that earlier Homo groups—perhaps Neanderthals or early Homo sapiens—shared a longer, more interconnected timeline with Chinese fossils, prompting a rethink of migration routes and interbreeding patterns. Stringer cautions that Yunxian 2 “can help us resolve the big confusion around a patchwork of fossils dating from about 1 million to 300 thousand years ago.”

Conclusion

As paleoanthropology enters a digital era, Yunxian 2 stands as a reminder that our origins are still being assembled from fragments across continents. The prospect that East Asia played a central role in early hominin evolution invites renewed exploration, collaboration, and cautious optimism about the true shape of the human family tree.