Read for Sex? A Controversial Debate Goes On

In a time of hyper-polarization, a lighter but telling debate continues to surface: do men read for the thrill of attraction, or is the idea a stereotype that misses the broader truth about reading habits? A recent cultural volley—centered on a satirical column about male book lovers—frames the issue as a test case for how society talks about gender, desire, and literature. The question isn’t just about books; it’s about how we understand masculinity and reading in public life.

The Numbers Behind the Debate

Statistics can sometimes seem to miss the point, but they anchor the discussion. A Swedish survey released recently suggested that reading has fallen to its lowest level in decades, and early commentary leaned on the trope that men are particularly disengaged from books. Critics argue that singling out men risks reinforcing stereotypes, while supporters say the data highlight a real cultural shift that needs to be understood rather than denied. The conversation has evolved from “Who’s reading?” to “Why do we stop reading, and what signals do those choices send?”

Performative Reading and Cultural Snobbery

Media voices have debated whether the idea of reading “for the lay”—to attract a partner—belongs in serious cultural discourse. Some writers compare it to fans wearing band T-shirts to prove expertise, rather than engaging with the art itself. Others argue that reading, in public or private, is a social performance shaped by norms, flirtation, and curiosity. The satire points to a broader tension: can we criticize performative reading while acknowledging that all readers, at some level, draw meaning from social contexts and personal ambitions?

What About Lighter Pleasures?

Some critics suggest pairing reading with other pleasures—wine, food, and conversation—as a way to entice younger audiences back to books. A few voices in the debate propose reading not to impress but to enrich social experiences—think a glass of zinfandel while leafing through a cookbook or a novel. Others remind us that sex, alcohol, and culture intersect in complex ways, and reducing reading to a single motive risks erasing the varied reasons people pick up a book: curiosity, empathy, escape, and learning.

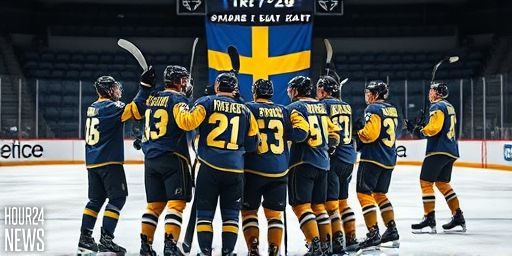

What It Means for Books, Festivals, and Public Culture

The conversation isn’t just about individual motives; it touches public life and culture economics. Could public support for writers be reimagined to reflect diverse reader communities? Some speculations even touch on high-profile cultural bets, asking what public investment in storytelling—such as a Zlatan Ibrahimović biography by a respected author—might do to national conversations about identity, sports, and literature. Would a high-profile biography shift reading priorities, or would it simply reflect a marketplace where sports and literature vie for attention?

Festival Floors and Policy Debates

Events like book fairs and literary festivals—such as those in Gothenburg—serve as laboratories for these questions. If the public sphere treats reading as a statement of identity, what happens when a festival leans into controversial books or provocative speakers? The debate becomes less about policing private desires and more about cultivating a culture where reading remains accessible, inclusive, and genuinely enjoyable for people of all backgrounds.

Rethinking Reading: Beyond Ladders of Sex and Snobbery

The essence of the discussion is not to normalize objectification or to glamorize crass motives. It’s to challenge ourselves to see reading as a spectrum of experiences—intellectual, social, sensual, and political. Encouraging broader access to literature, supporting diverse voices, and creating spaces where people can explore books without fear of judgment benefits everyone. After all, the core of reading culture should be curiosity, empathy, and connection, not a single stereotype about gender or motive.

Conclusion

So, is it really wrong to read for the “laying odds” of life? The answer, as the public discourse suggests, is nuanced. The real task is to expand what counts as reading motivation, to resist caricatures, and to ensure that literature remains a welcoming, multi-faceted pursuit for readers—men included—across generations and tastes.