Introduction: A World Beneath Our Feet

Earth’s surface water—lakes, rivers, and groundwater—has long defined our outlook on the planet’s vitality. But scientists are increasingly considering a far more expansive reservoir: water locked deep inside Earth since its formation. New evidence suggests that a significant share of the planet’s water may reside in the mantle and crust, far beneath our oceans. If confirmed, this discovery could rewrite theories about Earth’s early history and change how we think about future water resources.

What the Evidence Tells Us

Researchers analyze minerals that form under extreme pressures and temperatures, tiny hydrogen isotopes, and the behavior of fluids within rocks thousands of kilometers below the surface. Some studies point to water-bearing minerals that trap water molecules at great depths, resisting high heat and pressure. The implication is that water may have remained sequestered in solid materials since Earth accreted from a solar nebula, gradually migrating yet never surfacing in large quantities until geologic processes unlocked it. While measurements are challenging and interpretations debated, a growing chorus of geoscientists argues that deep Earth could be a substantial, ongoing water reservoir.

How Depth Changes Our Hydrological Model

Traditionally, models of Earth’s water cycle focus on surface and near-surface processes: precipitation, groundwater flow, and surface runoff. The idea of deep, long-reserved water adds a powerful new dimension. If the mantle and lower crust contain meaningful water stores, they could supply groundwater networks over geological timescales, influence volcanic activity, and affect mineral formation. This would also mean that surface water might be a smaller fraction of the planet’s total water than previously thought, with deep reservoirs acting as a slow, vast source that rebalance over millions of years.

Implications for Early Earth and Planetary Science

Hydrogen and oxygen, the core elements of water, are integral to planetary formation. If Earth began with hydrated minerals packed into its interior, early geologic processes could have liberated water gradually, helping to shape the atmosphere and early oceans. The concept aligns with observations of water in meteorites and the delivery of water-rich materials during accretion. By studying deep water, scientists can test hypotheses about how Earth acquired its oceans, how life-sustaining environments emerged, and how water cycles may have operated on other rocky planets, including Mars and exoplanets.

Potential Practical Benefits

Beyond theory, the prospect of substantial deep water carries practical implications. If future exploration confirms sizable deep-water stores, it could influence long-term water security strategies, mining, and geothermal energy development. Tapping into deep reservoirs would require careful, low-impact methods to avoid triggering seismic events or depleting fragile deep ecosystems. The reframing could also shift conservation priorities: safeguarding both surface and deep-water systems becomes a more holistic mission for governments and scientists alike.

What Comes Next for Research

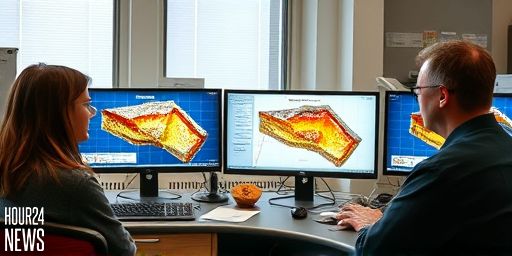

Advances in high-pressure laboratory techniques, deep-dive seismic methods, and computer simulations will be essential to separating competing ideas from robust evidence. New missions may target the deepest rocks, using innovative sensors to detect water’s fingerprint in minerals and fluids under Earth’s extreme conditions. As data accumulate, the scientific community will refine estimates of deep-water volume and distribution, clarifying how much of Earth’s water budget resides beneath our feet and how it might influence the future of Earth science.

Conclusion: A More Water-Rich World, Hidden in Plain Sight

The possibility that Earth harbors large-scale water reserves deep underground invites a more integrated view of our planet’s history and future. If deep water proves substantial, it could explain how Earth maintained habitability through eons of change and offer new avenues for securing water resources without extensive surface disruption. While many questions remain, the prospect underscores the importance of exploring the planet beneath us, where some of Earth’s most vital resources may lie waiting to be understood.