Galamsey, elites, and the economics of survival

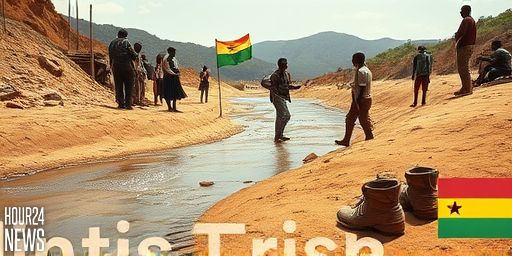

Ghana’s gold belts, long celebrated for wealth and opportunity, have become flashpoints where survival instincts clash with environmental and social costs. A December 15, 2025 opinion piece in the Daily Graphic titled “Beneath the surface. Tales of galamsey from Ayanfuri” offers a full-page investigation into why areas with known gold deposits attract galamseyers even when the risks are acknowledged. The investigation sheds light on the stubborn link between poverty, unemployment, and the allure of a sector that, in practice, often leaves a trail of ecological and social damage.

What drives people to risk the hazards of galamsey?

At the heart of the issue is economic pressure. In many mining communities, formal employment opportunities are scarce, wages are low, and social safety nets are thin. The appeal of galamsey—small, scalable dredging or hand mining that can be started with basic tools—presents a tangible path to income. For families that rely on seasonal harvests, mining income can be the difference between feeding children and going hungry. The Daily Graphic investigation notes that even when residents understand the ecological dangers, the immediate financial return often overrides long-term concerns.

Small-scale mining as a livelihood strategy

Galamsey is not merely a criminal enterprise; in many cases, it is a livelihood strategy embedded in local economies. Households diversify income sources, cycling through farming, trading, and informal mining depending on weather, market prices, and policy environments. When formal employment collapses, the galamsey option can look like a pragmatic choice. This reality complicates simple calls for enforcement and punishment, prompting policymakers to address root causes: poverty, lack of access to land rights, insecure tenure, and limited financial services that could formalize and regulate the trade without destroying livelihoods.

The role of elites and power structures

The Daily Graphic piece hints at a troubling complicity: elites who hold political influence or economic power may benefit from the galamsey economy either directly or through patronage networks. When protection, licenses, or contraband pathways exist, communities experience uneven enforcement and inequitable risk. The phenomenon is not unique to Ayanfuri; it resonates in many mineral-rich areas where governance challenges intersect with local ambitions and national revenue models. Elites can shape outcomes by controlling access to land, distributing permits, or smoothing over conflicts between small-scale miners and larger industrial players.

Policy gaps and enforcement challenges

Efforts to curb illegal mining often revolve around enforcement: mobilizing anti-galamsey squads, banning the use of riverine dredges, or cracking down on equipment. Yet without parallel investments in alternative livelihoods, miner training, credit facilities, and formalized small-scale mining cooperatives, bans can push activity underground rather than eliminating it. The question for Ghana is how to align environmental protection with economic survival, so that communities are not forced into a binary choice between visible ruin and invisible poverty.

Towards sustainable solutions

Building resilience requires a multi-pronged approach. First, targeted social protection and microfinance can help families weather price shocks and transition away from dangerous practices. Second, formalization—through clear licensing, transparent revenue sharing, and accessible financing—can bring miners into the safety net without erasing livelihoods. Third, investing in local processing facilities, responsible mining technology, and environmental restoration projects can create green jobs and rebuild trust with communities affected by galamsey activities.

What this means for the future of Ghana’s gold belt

The Ayanfuri narrative and similar pieces underscore a fundamental truth: sustainable economic survival in mining regions requires more than law-and-order approaches. It demands inclusive development that addresses the needs of families who count on mining for daily sustenance while protecting water sources, soils, and ecosystems for future generations. When elites, policymakers, and miners coordinate around risk-sharing and accountability, Ghana can steer its gold wealth toward durable prosperity rather than episodic gains.

Conclusion

Galamsey is a symptom and a signal—of poverty, opportunity, and the complex power dynamics that govern resource-rich communities. The December 2025 investigation serves as a call to construct policies that safeguard livelihoods, empower small-scale miners within formal frameworks, and reduce harm to the environment. Only through holistic, inclusive strategies can Ghana transform its gold belts from zones of conflict to corridors of sustainable development.