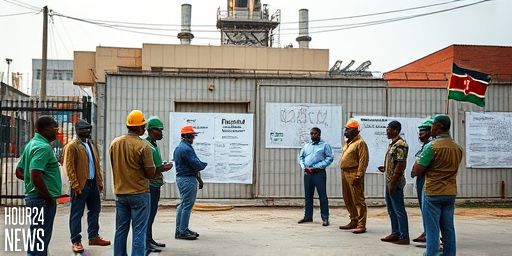

Overview: a high-profile shutdown shocks Kenya’s clean energy scene

Koko Networks, once a leading name in Kenya’s clean cooking revolution, has abruptly shut down its Kenyan operations. The collapse, reported by multiple sources, leaves more than 700 employees out of work and endangers the primary clean-energy option for hundreds of thousands of low-income households that depended on the company’s ethanol cooking fuel (ECF). The move reverberates beyond a single business, posing questions about how Kenya can sustain affordable, low-emission cooking as the country pursues its climate and energy goals.

When Koko Networks entered the market, it offered a promising model: distribute clean-burning ethanol-based fuels through accessible refill stations, aiming to reduce household air pollution and broaden energy access. In its heyday, it drew attention from investors, policymakers, and development partners who saw a scalable approach to cleaner cooking in East Africa. Today, those hopes are tempered by the sudden shutdown and its immediate human and economic costs.

Impacts on workers and households

The immediate consequence is stark: more than 700 employees have lost their jobs, many of them middle- and lower-income workers who found opportunity in Kenya’s fast-growing cleantech sector. Beyond the employees themselves, thousands of suppliers, technicians, and service providers connected to Koko’s operations face uncertainty as the supply chain contracts.

For households, particularly low-income families relying on affordable ethanol fuels, the shutdown threatens a return to more polluting or less affordable options. In urban and peri-urban areas where Koko had established a distribution network, families may have to switch to traditional firewood, charcoal, or imported cooking fuels if alternatives aren’t readily accessible. The short-term disruptions risk undermining progress toward reduced indoor air pollution and household energy burdens and could slow Kenya’s broader clean energy transition.

What went wrong? Possible factors behind the collapse

While full details are still emerging, several factors tend to accompany sudden closures of energy startups in emerging markets. Financing challenges—ranging from debt service pressures to shifts in donor or investor appetite—can force difficult restructuring. Operational hurdles, including maintaining a dense network of refill points, ensuring fuel quality, and navigating regulatory requirements, can also escalate costs and trigger a downturn if revenues fail to meet projections. Market competition, pricing pressures, and macroeconomic headwinds (currency fluctuations, inflation, and rising interest rates) further complicate a business model that relies on affordable upfront capital and steady cash flow.

Industry observers note that maintaining predictable fuel supply chains is crucial for ethanol-based cooking programs. Inconsistent supply, price volatility, and service disruptions can erode consumer trust and push households toward alternative fuels. The Kenyan government and development partners have emphasized clean cooking access as a priority; a collapse of a major provider underscores the need for resilience measures, diversified fuel options, and social protection for workers and customers during transitions.

What happens next: policy responses and support mechanisms

In the wake of such events, policymakers and industry stakeholders typically explore several avenues. For workers, government or partner organizations may offer severance packages, retraining programs, and job placement assistance to ease the transition. For households, targeted subsidies or social safety nets may be mobilized to prevent a sudden switch to highly polluting fuels. Regulators may also scrutinize licensing, safety, and environmental compliance to prevent future disruptions and to ensure clean cooking remains accessible and affordable.

Investors and lenders may reassess risk across the sector, potentially leading to more cautious deployment of capital or a push toward more robust business models that can ride volatility. In Kenya’s broader energy agenda, the incident could spur greater emphasis on resilience: blended portfolios of fuels, robust distribution networks, and stronger protections for workers and consumers during high-uncertainty periods.

Conclusion: balancing ambition with resilience in Kenya’s clean energy journey

The shutdown of Koko Networks marks a sobering moment for Kenya’s clean energy ambitions. It highlights the fragility of rapid-scale models in volatile environments and underscores the need for safeguards that protect workers and households while sustaining progress toward a low-emission future. As Kenya and its partners assess lessons learned, the path forward will likely hinge on diversified funding, resilient distribution networks, and policies that ensure both energy access and economic security for communities most dependent on clean cooking solutions.