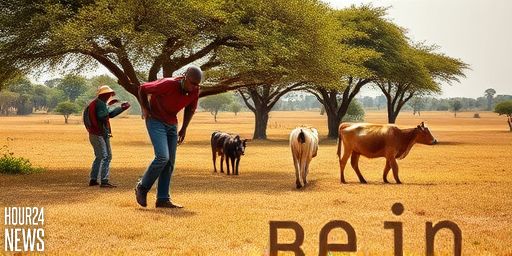

Indigenous trees and climate resilience: a potential game changer for Benin

In Benin’s drylands, where hot days stretch across vast stretches of land, dairy farming faces mounting climate pressures. The latest study highlights a simple, nature-based solution: leveraging indigenous trees in pasturelands to build resilience against drought, heat, and forage scarcity. This approach, rooted in traditional knowledge and modern ranching needs, could help secure livelihoods for millions of small-scale herders and dairy producers who manage roughly 70% of the country’s land with sparse pastures and scattered trees.

The core idea is agroforestry—integrating trees with pasture to deliver multiple benefits. Indigenous species adapted to Benin’s climate can improve soil health, reduce soil erosion, enhance moisture retention, and provide shade and fodder during critical periods. By combining trees with grazing lands, farmers may sustain higher milk production while using natural systems that require fewer external inputs, such as scarce veterinary medicines or synthetic supplements during droughts.

Why trees matter in a warming, arid landscape

Benin’s drylands are characterized by high temperatures, irregular rainfall, and degraded pastures. In this context, the availability of nutritious fodder declines seasonally, and heat stress can reduce cattle productivity. Indigenous trees, adapted to local conditions, can mitigate these challenges by:

- Providing year-round forage through leaves and pods, especially during the long dry season.

- Shading livestock to lower heat stress, which is closely linked to better feed intake and milk yields.

- Improving soil structure and moisture retention, supporting more resilient grass growth after rainfall events.

- Offering additional ecosystem services such as windbreaks and habitat for pollinators, which strengthen overall farm resilience.

Farmers interviewed in the study indicated that trees are not just a backdrop but a functional part of the dairy system. Decades of experience show that mixed-species agroforestry can stabilize production cycles and reduce vulnerability to climate shocks. The new research quantifies and formalizes these benefits, providing evidence that trees can be integrated without sacrificing land area for grazing.

From field observations to scalable practices

The study combines on-the-ground farm trials with community knowledge to identify practical configurations. Key findings include selecting indigenous species that balance fodder value with ecological compatibility, planting layouts that minimize competition with forage grasses, and maintenance practices that protect soil health.

For instance, researchers recommend staggered tree belts along pasture boundaries and within paddocks to create microclimates that support both forage growth and livestock comfort. The trees’ root systems also contribute to soil stability and nutrient cycling, buffering pastures from erosion during heavy rain events and allowing for more reliable pasture recovery after droughts.

Adoption hinges on farmer-friendly incentives and knowledge-sharing networks. Farmers emphasized the need for accessible seeds or saplings, simple maintenance regimes, and local extension services that translate scientific findings into practical guidelines. The study’s authors call for pilots at scale, with monitoring to track milk production, animal health, and pasture productivity over multiple seasons.

The potential gains are not limited to productivity. Agroforestry can diversify farm income through nuts, fruit, or timber from indigenous trees, while contributing to climate adaptation goals and biodiversity conservation. In Benin’s context, where climate risks are increasingly pronounced, such diversification can be a safety net for rural households.

Policy and practice: paving the way for wider use

To move from pilots to widespread adoption, policy support will be essential. This includes financial incentives for trees on farms, access to drought-tolerant seedling programs, and training that blends traditional knowledge with modern husbandry practices. Collaboration between researchers, farmers, and government agencies could establish best-practice guidelines that are accessible in local languages and tailored to regional variations within Benin.

Ultimately, the study paints a hopeful picture: by reintegrating indigenous trees into Benin’s dairy landscapes, farmers can build climate resilience while maintaining productive herds. The approach aligns with broader sustainable agriculture goals and offers a practical pathway for resilience in one of West Africa’s most challenging environments.