Understanding Lava Worlds and Their Extreme Environments

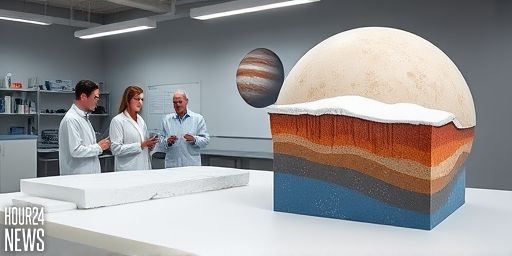

Lava worlds are among the most extreme exoplanets scientists study. These rocky planets orbit very close to their stars, where intense irradiation melts the dayside crust into a persistent magma ocean. In such worlds, the surface is a dynamic boundary between molten rock and the cooler, partially solidified crust, shaped not only by the star’s heat but also by the planet’s own internal heat and gravitational interactions with its star.

Why Tidal Heating Matters on Short-Period Planets

When a planet orbits with even a modest eccentricity—only a few percent—its distance from the star varies over the year. This variation generates tidal forces that flex the planet, injecting heat deep into its interior. On lava worlds with magma oceans, tidal heating compounds stellar irradiation, potentially sustaining or renewing magma convection and stirring the ocean-like surface layer. This deep heating can influence volcanic activity, magma viscosity, and the overall thermal structure of the day-side hemisphere.

Mechanical Waves: From Magma to the Sky

In a magma ocean, vigorous convection can spawn large-scale waves that propagate across the molten surface. These waves are not mere curiosities; they transport heat, redistribute molten material, and interact with the top of the crust. As tidal forces drive oscillations, you can imagine crests and troughs of molten rock moving in cycles driven by orbital timing. The result is a complex, time-variable surface chemistry and a shifting pattern of lava lakes, crustal patches, and emissivity such that a single, static “lava flow” picture cannot capture the reality of these worlds.

Thermal Variability Across the Dayside

The day side of a lava world experiences the strongest irradiation, creating a thermal gradient from the hotspot to the limb and nightside. Even within a few percent of eccentricity, the tidal heating can modulate this gradient, leading to diurnal and orbital-phase variability. Observers would expect fluctuations in infrared brightness as the magma ocean’s surface temperature responds to changing heating rates. Layering within the magma—crystallizing crust beneath a partially molten surface—can create a stratified temperature profile, further complicating the observable signal.

Observational Signatures and Implications

Detecting these phenomena hinges on precise infrared measurements and phase curves that map temperature changes over an orbital period. If tidal heating is substantial, you may see enhanced thermal emission during certain orbital phases or episodic brightening tied to periastron passages. The interplay between tidal heating and irradiation also affects the chemical signatures detectable in secondary eclipses or transit spectroscopy, as outgassed species from the magma ocean modify surrounding atmospheres or exospheres.

Modeling the Coupled System

To understand magma ocean waves and thermal variability, researchers build coupled models that simulate tidal deformation, heat transport in molten rock, crust formation, and the radiative response of the dayside. Key parameters include the planet’s orbital eccentricity, rotation rate, magma viscosity, and the efficiency of heat loss to space. By exploring a range of plausible eccentricities within current observational bounds, scientists can predict how vigorous the magma ocean waves are and how rapidly the surface temperature responds to tidal forcing.

Why This Matters for Exoplanetary Science

These studies reveal how small orbital tweaks can drive large-scale surface dynamics on lava worlds. Understanding magma ocean waves and thermal variability helps explain the diversity of exoplanet atmospheres (or their absence), informs the interpretation of infrared phase curves, and guides the search for exotic planetary weather patterns in extreme environments. Moreover, it highlights the importance of tidal heating in shaping a planet’s geology and habitability prospects for worlds that push the boundaries of what we consider molten and dynamic.

Future Prospects

As observational capabilities improve, especially in the infrared, astronomers will test these models against real data. The next generation of telescopes promises higher-precision phase curves and spectral data that could reveal the fingerprints of a vigorously stirred magma ocean and the thermal heartbeat of lava worlds in tight orbits around their stars.