Uncovering a deep past: a genome from the ancient pathogen

Researchers have long debated where syphilis, caused by the bacterium Treponema pallidum, first took hold in human populations. A groundbreaking study now pushes the origin of this treponemal disease far back into the prehistoric Americas. By sequencing the genome of a 5,500-year-old Treponema pallidum specimen from what is now Colombia, scientists have opened a new window into how these pathogens spread and diversified long before written records.

What the ancient genome reveals

The ancient DNA analysis centered on a remarkably well-preserved sample from a time when human communities in the Americas were practicing early farming, trade, and complex social organization. By reconstructing the bacterial genome, researchers could compare ancient Treponema pallidum with modern strains observed in syphilis, yaws, and bejel. The comparisons suggest that treponemal diseases had already diversified in the Americas thousands of years ago, long before Europeans carried the disease to other continents.

Implications for the origin debate

Historically, scholars have argued for a Old World origin of syphilis based on late medieval European outbreaks and the subsequent global spread during exploration and colonization. The new findings add a compelling dimension to this discussion: treponemal pathogens were present in the Western Hemisphere well before contact with Europe, indicating that the syphilis lineage may have deep, regional roots in the Americas. This shifts the narrative from a single, recent introduction to a story of long-standing diversification of treponemes in the New World.

Disentangling syphilis, yaws, and bejel

Treponema pallidum is part of a broader group of closely related bacteria responsible for diseases such as yaws and bejel, which historically affected different climates and communities. The ancient genome provides clues about how these diseases relate to one another and why their clinical presentations vary so much across regions. Understanding their shared ancestry helps archaeologists and medical historians distinguish between outbreaks that resemble syphilis and those caused by related treponemes, which is crucial for accurate interpretation of ancient remains.

Methods: how the genome was recovered

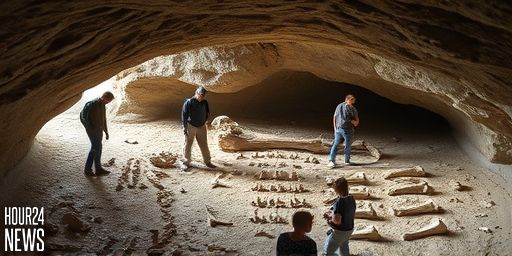

Recovering a high-quality genome from a 5,500-year-old specimen is a testament to advances in paleogenomics and meticulous lab work. The team extracted tiny fragments of bacterial DNA from the ancient bone sample, then used next-generation sequencing and careful computational filtering to assemble a complete genome. Modern DNA techniques, including contamination controls and comparative genomics, ensured that the reconstructed genome accurately reflects the ancient pathogen rather than modern microbes.

Why this matters for our understanding of disease history

By anchoring a syphilis-related genome in a prehistoric American context, the study reframes how scientists think about the emergence and spread of treponemal diseases. It suggests that populations in the Americas endured a long, dynamic history with treponemes, which may have shaped social networks, trade routes, and even cultural practices. For public health science, these insights illuminate how ancient pathogens adapt to human hosts and ecosystems, information that can inform contemporary disease surveillance and research into therapeutic targets.

Looking ahead

Future work will aim to locate more ancient treponemal genomes from diverse regions and time periods. By building a broader genetic map of Treponema pallidum and its relatives, researchers hope to resolve lingering questions about migration patterns, cross-continental transmission, and the ecological factors that favored the emergence of distinct treponemal diseases. The story of syphilis may be more intricate and longer-lived than previously imagined, stretching across the prehistoric landscape of the Americas.