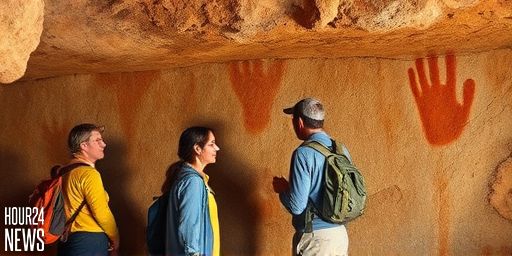

Discovery of the Hand Stencils

In a remote limestone cave on a speck of Indonesia’s vast archipelago, researchers uncovered a pattern of faint ochre hand stencils pressed against weathered rock. The marks, created when a hand was pressed flat to a wall and pigments rubbed or blown around the fingers, are among the oldest known forms of human artistic expression. A collaborative effort between Australian and Indonesian scientists analyzed the pigments and cave context to determine when these images were made, aiming to place them within the broader story of early art and culture.

What the Evidence Suggests

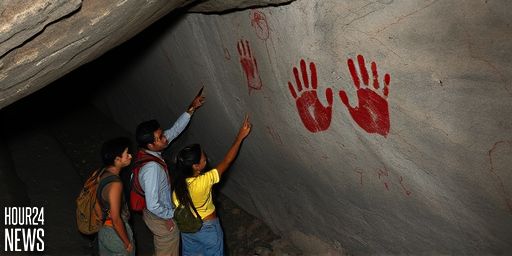

The team’s examination focused on the pigment composition, mineral grains, and the depth of weathering on the stencils. The ochre used in the drawings is consistent with pigments found in other parts of the region, suggesting exchange or shared material knowledge among early communities. The careful layering of pigments, along with the technique of creating negative silhouettes by hand, indicates a deliberate and repeated act—signs that the site was more than a casual shelter but a space for symbolic or communicative activity.

Several stencils show a range of sizes and orientations, implying multiple individuals contributed to the wall art over time. This challenges earlier assumptions that ancient cave imagery was the domain of a single creator or limited to a brief moment in prehistory. Instead, the cave appears to have functioned as a communal canvas, with successive generations adding their marks and perhaps embedding social or ritual meaning into the space.

Dating the Images and Its Significance

Determining the age of these hand stencils involved a combination of radiometric dating on mineral accretions over and around the pigments, along with stratigraphic analysis of the cave deposits. By dating the mineral layers and cross-referencing with regional archaeological sites, researchers estimate the stencils were created tens of thousands of years ago. If confirmed, they would stand as some of the earliest examples of cave art anywhere in the world, potentially reshaping timelines for when modern humans began to engage in symbolic representation beyond utilitarian need.

Experts emphasize that these findings should be integrated with broader patterns of human movement in Southeast Asia during the late Pleistocene. The presence of such ancient imagery in this locale could reflect early migrations, cultural diffusion, or parallel development of artistic behavior independent of other well-documented regions. What remains clear is that Indonesia’s caves may hold a more complex record of early human creativity than previously understood.

Why This Changes Our Understanding

The discovery contributes to a growing body of evidence that symbolic thinking emerged in multiple regions at roughly comparable times. Hand stencils, as a simple yet powerful form of expression, reveal that early humans prioritized communication, identity, or group cohesion through image-making. As researchers publish more data and improve dating techniques, we can expect a clearer picture of how and when these early artists began to leave their marks on natural walls, sharing stories, beliefs, or shared knowledge with others in their communities.

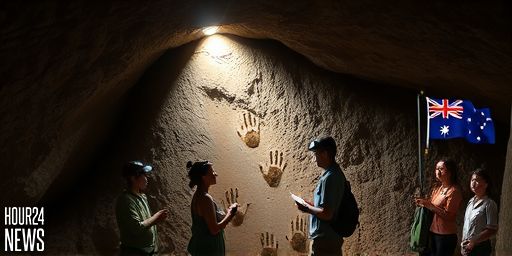

Looking Ahead

Further excavations and analyses in this Indonesian cave and other sites across the archipelago are planned to refine dating and interpretation. The collaboration between Australian and Indonesian researchers demonstrates the value of international teamwork in uncovering humanity’s distant past. Each new piece of evidence helps illuminate the origins of art, culture, and the human impulse to leave a mark on the world for future generations to study.