Ancient Handprints Reimagined

Scientists are rethinking the timeline of human creativity after reporting what may be the world’s oldest known cave art. In a largely unexplored region of Indonesia, researchers found stencil-like handprints on cave walls that are estimated to date back at least 67,800 years. The discovery, announced by a collaboration of Indonesian and Australian researchers, could push back the origins of symbolic expression by modern humans and offer a new window into early artistic behavior.

Why These Prints Matter

Hand stencils are among the simplest yet most powerful forms of prehistoric art. They require a basic understanding of space, proportion, and the motor skills to apply pigment to a surface. When combined with dating techniques, such as uranium-series dating of mineral deposits on the prints, they can reveal when humans first engaged in a deliberate act of self-expression. If confirmed, the Indonesian prints would precede a widely cited collection of cave art in Europe and the Americas by tens of thousands of years, reshaping assumptions about the geographic origins of creativity.

How the Dating Was Done

The team used a combination of geochemical dating, pigment analysis, and careful stratigraphic work to establish the age of the prints. The tan pigments, likely derived from minerals available in the region, were examined for their mineralogy and microstructure. Crucially, researchers looked for the presence of mineral crusts that formed after the handprints were applied, which allowed them to estimate a minimum age. While dating cave art across the globe often hinges on rare artifacts or creature renderings, the Indonesian prints benefit from multiple independent dating signals that strengthen the case for great age.

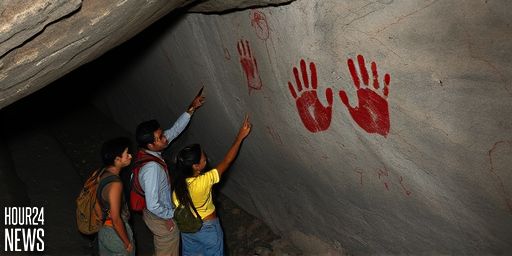

Interpreting the Imagery

Unlike some cave art that depicts animals or human figures in detailed scenes, these prints are abstract silhouettes that evoke the act of making a mark. Anthropologists say such depictions offer a glimpse into early human cognition: a desire to leave marks, perhaps as a record, a ritual, or a form of communication. The careful placement and even distribution of the prints within a sheltered rock shelter suggest intentional placement rather than accidental dispersion by wind or water. This pattern hints at a systematic practice, which is a cornerstone in arguments that early humans were engaging in culturally meaningful activities beyond survival tasks.

Context within the Global Timeline

Whether these Indonesian prints are definitively the oldest cave art remains a matter of ongoing research and scholarly debate. The discovery sits within a broader conversation about when symbolic behavior emerged and how early humans spread across different continents. Some researchers argue for parallel development of art and symbolic thought in multiple regions, while others posit a more uneven timeline driven by environmental and social factors. Regardless of where the exact edge lies, the Indonesian site adds a crucial data point that broadens the geographic map of early human creativity.

What Comes Next for Researchers

Further fieldwork in the limestone caves is planned to locate additional prints and collect more precise dating samples. Advances in non-destructive testing, pigment analysis, and micromorphology will help refine the age estimates and the cultural significance of the site. There is also interest in examining whether similar stencil traditions exist in neighboring areas, which could reveal broader networks of artistic practice among ancient populations in Southeast Asia.

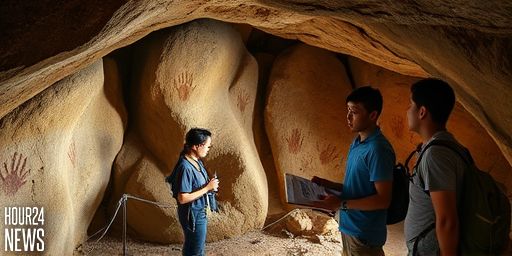

Conservation and Public Education

As with other ancient sites, preservation is a priority. Protecting fragile pigments and cave interiors from exposure and vandalism will be essential to ensure that researchers can continue to unlock the story of humanity’s earliest storytellers. The emergence of such discoveries invites museums, educators, and local communities to engage with deep-time art in a way that is respectful of the landscape and the people who inhabit it today.