What is the Doomsday Glacier?

The so-called Doomsday Glacier, formally known as Thwaites Glacier, sits on the western edge of Antarctica and acts as a massive ice barrier for the ice sheet behind it. Its size and location make it a critical hinge on the continent’s ice dynamics, influencing how fast ice can flow toward the ocean. In recent weeks, scientists have detected hundreds of earthquakes in the region surrounding Thwaites, sparking questions about how these tremors may influence the glacier’s stability and the broader implications for future sea level rise.

Why are earthquakes affecting Thwaites now?

The harsh, dynamic environment around Thwaites is shaped by the interactions between ocean water, bedrock, and thick ice shelves. Some researchers suggest that deep, under-ice processes, tectonic stress, and the grounding line’s response to warming ocean water could all contribute to seismic activity in the area. While earthquakes are a natural geophysical phenomenon, their timing near a fragile ice mass raises interest in whether the tremors could hasten calving, alter ice flow, or trigger subglacial changes that affect how quickly ice enters the ocean.

What this could mean for sea levels

Thwaites Glacier is a keystone in the global sea level equation. Even modest changes in its behavior could translate into faster or slower contributions to sea level rise. If earthquakes or related under-ice processes accelerate ice discharge, coastal cities around the world—especially those in low-lying delta regions—could face higher flood risks in coming decades. Conversely, the relationship between seismic activity and ice dynamics is complex and not yet fully understood. Scientists emphasize that a single event or cluster of earthquakes does not determine the glacier’s fate, but it does spotlight the need for continued observation and modeling to refine sea level projections.

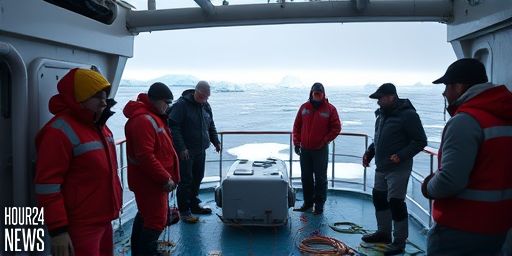

What scientists are doing now

Researchers are employing an array of tools to monitor Thwaites: ocean-bottom sensors, satellite radar, ice-penetrating radar, and high-precision GPS networks. These instruments help scientists track how the glacier’s grounding line moves, how the surrounding water temperatures change, and how ice shelf integrity evolves over time. International collaborations are accelerating data sharing and analysis, aiming to improve risk assessments for coastal communities and to understand how natural seismic activity might interact with climate-driven ice loss.

Monitoring methods

Seismic networks placed around Antarctica can capture tremor patterns, while satellite data reveal surface displacements and calving events. Ocean data show how much heat is entering the water beneath the glacier, a key driver of melting from below. Together, these datasets enable researchers to test hypotheses about whether earthquakes directly influence ice dynamics or simply reflect a background process in a highly active system.

Uncertainties and timelines

Experts caution that short-term tremor bursts do not automatically portend rapid disintegration. The glacier’s response may unfold over years or decades, and modeling requires careful calibration against multiple variables, including ocean temperatures, atmospheric warming, and bedrock topography. The scientific goal is to translate observations into probabilistic forecasts that help policymakers and coastal planners manage risk while avoiding alarmism.

Bottom line for the public

The news that Thwaites is experiencing seismic activity underscores the interconnectedness of Earth systems. It reminds us that Antarctica’s ice sheets do not exist in isolation but are part of a global climate and ocean network that ultimately shapes coastal flood risk. Ongoing research will refine predictive models and improve resilience planning for communities worldwide, ensuring preparedness even as the science continues to evolve.