Introduction: A new mechanism behind a familiar motion

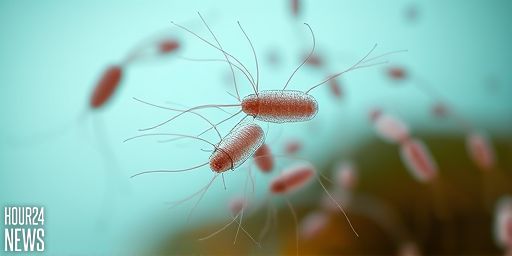

Bacteria swim by rotating tiny tail-like structures called flagella. For decades, scientists have relied on chemical signals and molecular timers to explain why these microorganisms switch from go-straight to tumble-and-reorient. Recent research, however, points to active mechanical forces within the cell as a key driver of swimming-direction changes. This perspective enriches our understanding of one of biology’s most studied molecular machines: the bacterial flagellar motor.

Flagella, motors, and the thrill of turning

Each bacterium in many species harnesses a flagellum powered by a rotary motor embedded in the cell membrane. The motor can switch rotation directions, which, in turn, alters the trajectory of the cell. When all flagella rotate in concert, the bacterium swims smoothly in a straight line. If rotation becomes stochastic or oppositional across the flagellar bundle, the bundle may disrupt the forward run, causing the cell to tumble and reorient itself.

Traditionally, researchers have focused on chemical cues guiding these switches, such as gradients of attractants or repellents detected by receptors. The latest work shifts attention to how internal mechanical forces within the motor complex influence the direction decision, suggesting that the cell exerts and responds to forces in real time to change course.

The role of mechanical forces inside the motor

Inside the flagellar motor, proteins assemble into a dynamic rotor-stator system. The torque generated by this ensemble is not simply a chemical switch but a mechanical negotiation. Active forces—produced by ion flux, conformational shifts in rotor proteins, and interactions with stator units—shape how easily the motor switches from counterclockwise to clockwise rotation. When a cell experiences certain internal stresses, the torque balance shifts, nudging the system toward a tumble mode or toward a stable straight run.

What this means is that the bacterium’s immediate physical environment and its internal state can subtly bias the torque landscape. The motor effectively samples mechanical states and uses them to decide whether to maintain direction or pivot. This perspective aligns with growing evidence that molecular machines operate not in a vacuum of chemistry but within a crowded, force-filled cellular milieu.

How active forces influence tumbling and reorientation

During a run, flagella rotate in a cooperative fashion to propel the cell forward. For a tumble to occur, some flagella switch direction, toss the bundle into a chaotic configuration, and cause the cell to reorient. The new mechanical-insight model proposes that these direction changes aren’t solely a product of chemical signaling; they are also guided by the mechanical feedback the motor receives from its own structure and from surrounding cytoplasmic forces.

Experimentally, researchers are measuring how changes in internal tension, ion flow, and protein conformation correlate with abrupt shifts in swimming path. They have begun to map a spectrum of motor states that correspond to different torque outputs, showing that the bacterium can bias the direction change toward a tumble with particular physical cues, even before chemical signals fully propagate through the network of receptors.

Why this matters for biology and beyond

Understanding the mechanical side of flagellar switching completes a more holistic picture of bacterial locomotion. It helps explain how bacteria respond rapidly in fluctuating environments, from navigating toward nutrients to escaping harmful conditions. The findings also enrich the broader study of nanomachines, giving engineers a template for how force generation and mechanical feedback can be integrated into synthetic rotary systems that operate at microscopic scales.

In practical terms, this research could influence how scientists model microbial behavior in complex ecosystems, design targeted antimicrobials that disrupt motor mechanics, or inspire bio-inspired propulsion systems for micro-robots that traverse liquid environments with finesse and resilience.

Looking ahead

The field is moving toward a more integrated view of bacterial locomotion, where chemical signals, mechanical forces, and stochastic fluctuations all contribute to the final act: a direction change. As new imaging and biophysical tools come online, researchers expect to reveal even finer details about how active mechanical forces within the flagellar motor shape the life of a microbe, one tumble at a time.