New Milestones from a Chilean Mountaintop

In the high deserts of northern Chile, the Vera C. Rubin Observatory has begun a new era of asteroid astronomy. Since its first light last spring, the giant telescope—nestled on a dark mountaintop with a sweeping view of the sky—has already delivered discoveries that excite planetary scientists and space enthusiasts alike. Among the most striking findings is the detection of the fastest-spinning asteroid ever observed, a world that proves the Rubin Observatory can reach beyond the boundaries of what we thought possible in small-body science.

What makes this asteroid extraordinary

Asteroids spin for a variety of reasons, from past collisions to internal structure. The record-breaking object observed by Rubin is spinning so rapidly that it challenges conventional ideas about what constitutes a “rubble-pile” asteroid—loose aggregates held together only by gravity and weak cohesive forces. Its quick rotation implies a robust interior, or alternatively, a unusual shape and reflective properties that make its rotation easier to measure with Rubin’s sensitive detectors.

Researchers emphasize that the discovery is not just about a fast clock. The asteroid’s size matters: its large diameter—likely several hundred meters—combined with such a rapid spin raises questions about how it formed and how it could have survived past disruptive events. These clues can illuminate the broader population of near-Earth objects and help scientists assess potential impact risks, while also offering a window into the early solar system’s dynamics.

Why Rubin’s first-light success matters

The first light images from the Vera Rubin Observatory stunned the astronomy community with their clarity and depth. The telescope’s wide field of view and powerful camera allow it to capture thousands of objects each night. In the case of the fast-spinning asteroid, Rubin’s data provide precise rotation rates, shape inferences, and surface properties that smaller observatories can struggle to obtain. This is a strong reminder that the Rubin facility is not just a larger version of existing instruments; it is a fundamentally different tool for tracking small bodies across the sky.

Implications for planetary science and defense

Understanding rapid rotators helps scientists refine models of asteroid internal structure and cohesion. If such bodies are common, it could signal that many near-Earth asteroids have solid, monolithic interiors rather than being loose piles of rubble. This has implications for how they evolve over time, how they respond to gravitational interactions, and how they would fare in any hypothetical mitigation scenarios. While the discovery is primarily a boon for science, it also contributes tangentially to planetary defense by improving the accuracy of simulations that predict asteroid behavior under various forces.

The Rubin Observatory edge: capabilities on show

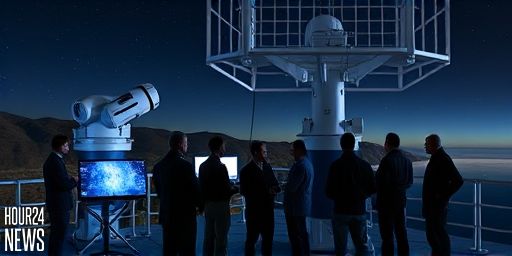

Located in the Chilean Andes, the Rubin Observatory is designed to survey the sky with unprecedented tempo and depth. Its software stacks, data processing speed, and automated follow-up enable scientists to respond quickly to intriguing findings like the fastest-spinning asteroid. As it continues to collect data, researchers expect a flood of new measurements that could reveal a wider diversity of spinning states, shapes, and surface features among the asteroid population.

What to watch for next

As the Rubin team sifts through terabytes of nightly imagery, astronomers will refine rotation periods for the record-holder and search for similar objects that exhibit extreme spins. The observatory’s ongoing survey strategy makes it likely that other fast rotators will be identified, offering comparative cases to test theories about formation and structural integrity. In parallel, scientists will study how observational biases may affect the detection of ultra-fast rotators, ensuring that future catalogs accurately reflect the true distribution of spin rates in the solar system.

In short, the Vera Rubin Observatory’s first light has already delivered a headline-worthy discovery: the fastest-spinning asteroid ever seen. More importantly, it demonstrates the telescope’s transformative potential to illuminate the small-object zoo that circles our planet, turning a Chilean mountaintop into a doorway to new solar system knowledge.