Introduction: A New Benchmark in Asteroid Spin Rates

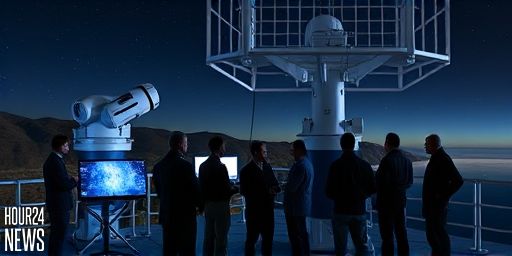

The Vera C. Rubin Observatory, perched on a Chilean mountaintop, has begun a new chapter in planetary science. As its powerful telescope conducts rapid, wide-area surveys of the night sky, astronomers have detected the fastest-spinning asteroid ever observed. The discovery not only sets a record for rotation speed but also raises intriguing questions about the structure and composition of small bodies in the solar system.

The Observatory’s First Light and What It Teaches Us

Since its first light last spring, the Rubin Observatory has delivered images and data that stunned the astronomical community. Built to map the sky with unprecedented depth and cadence, the facility is already catching fleeting events that were previously difficult to observe. The first light images provided proof of concept: a telescope capable of tracking subtle brightness variations across thousands of objects in a single night. Among these observations, a distinctly fast rotor stood out, rotating far more quickly than typical asteroids of similar size.

How Fast Is Fast? The Significance of a Record-Spinning Asteroid

Asteroids spin due to collisions, internal strength, and tidal forces. Most small bodies rotate every few hours; some lose structural integrity if they spin too quickly. The newly observed asteroid, with a rotation period significantly shorter than most of its peers, challenges our understanding of what holds these rocks together. Scientists will study its light curve—the variations in brightness as the object spins—to infer its shape, porosity, and possible binary nature. In turn, this informs models of asteroid composition and the evolutionary history of the solar system.

What This Means for Theories of Asteroid Structure

Record spin rates push researchers to rethink whether tiny asteroids are monolithic rocks or piles of rubble held together by gravity and cohesion. If the Rubin Observatory’s object maintains its speed without breaking apart, it could imply unusual internal strength or unusual shape. Conversely, if it fragments over time, the event will offer a rare natural laboratory to study the mechanics of disruption and the distribution of debris in near-Earth space. Either outcome will refine predictive models used by planetary defense programs and space mission planners.

Rubin Observatory’s Role in a New Era of Discovery

The ongoing survey work from Chile is designed to catalog billions of stars and countless small bodies across the solar system. The fast-rotating asteroid showcases the kind of high-impact science Rubin enables: deep, repeated surveys that reveal transient, time-sensitive phenomena. As data streams continue to pour in, astronomers anticipate discovering more fast rotators, binary systems, and unusual objects whose peculiarities can be traced to formation environments across the early solar system.

Looking Ahead: How Researchers Will Validate the Findings

Verification will involve follow-up observations using Rubin’s network of spectrographs and possibly collaboration with other observatories around the world. By combining light curves, spectral data, and radar ranging when available, scientists aim to build a comprehensive picture of this asteroid’s size, shape, density, and surface properties. The result will be more than a single record; it will help calibrate the thresholds that define what makes an asteroid resilient or fragile under extreme rotation.

Conclusion: A Sommation of Promise from a Global Telescope

The Vera C. Rubin Observatory’s first light heralds a transformative period in astronomy. The fastest-spinning asteroid discovery underscores the telescope’s transformative capability to monitor the dynamic sky. As data accumulate, researchers expect to unlock further surprises about small bodies, their origins, and their destinies in the solar system—and to push the boundaries of what we thought possible in asteroid science.