Introduction: A Remarkable Discovery in Chilean Mines

Archaeologists have unveiled a chilling window into ancient mining life in northern Chile. A naturally preserved mummy, dating back about 1,100 years, was uncovered in a turquoise-rich mining region. Recent CT scans provide a startling narrative: the man did not die of illness or exposure alone, but from extensive blunt-force trauma consistent with a rockfall or mine collapse during turquoise extraction. This discovery adds a new layer to our understanding of early mining hazards and the social organization around turquoise work in pre-Columbian societies.

How CT Scans Rewrote the Story

Advanced computed tomography allowed researchers to peer inside the mummy without disturbing the delicate remains. The scans reveal a pattern of injuries that indicate a violent encounter with falling rock or collapsing mine structures. Although the exact circumstances remain debated, the injury distribution strongly suggests death caused by a mining accident rather than a prolonged illness or sudden trauma from other activities. The use of CT imagery helps distinguish perimortem injuries (those occurring at or around the time of death) from postmortem damage, strengthening the case for a mine-related fatality.

What This Tells Us About Ancient Turquoise Mining

The subject’s age and context point to a broader practice in the region: turquoise mining was likely a significant economic and cultural activity. Turquoise ores were prized for their color and symbolic value, often linked to status, trade, and ritual use. The combination of a well-preserved tomb and a clear cause of death suggests that miners faced real, physical dangers, including cave-ins and structural failures—risks that would have affected entire communities involved in turquoise procurement and export.

Interpreting the Social Context

1,100 years ago, mining would have been a collective effort. The presence of a single well-preserved individual with explicit signs of violent, accidental death could reflect a worker who died during a routine mining shift or a sudden collapse that trapped multiple laborers. Whether this mummified man held a particular role—such as a mine overseer, skilled extractor, or ritual participant—remains a topic for further study. Researchers are comparing this mummy’s skeletal markers with other regional burials to map occupational patterns and social hierarchies in ancient turquoise economies.

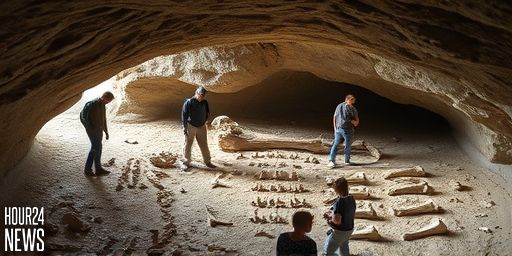

Preservation and What It Means for the Record

Preservation in arid desert environments is exceptional, and the Chilean site benefits from the dryness and mineral salts that stabilized soft tissues. The CT findings, coupled with careful osteological analysis, provide a rare, direct line to daily life in a prehistoric turquoise-mining landscape. Each data point—bone injuries, wear patterns, and the burial context—contributes to a more nuanced portrait of how early miners lived, worked, and faced danger underground.

Future Research Directions

Direct dating, isotopic analysis, and comparisons with other regional finds will help determine whether this incident was isolated or part of a broader mining episode. Scientists also aim to reconstruct the tools and techniques used by ancient miners, exploring how they tempered risks, whether through communal labor arrangements, safety practices, or spiritual rituals designed to appease deities connected with turquoise and the underworld.

Impact on Public Understanding

This discovery enriches our understanding of how resource extraction shaped early South American societies. It highlights the human cost of precious materials long valued across cultures and underscores the importance of interpreting archaeological finds with modern imaging methods to uncover accidents of the past. The 1,100-year-old mummy serves as a poignant reminder that antiquity’s technological acts—mining, labor, and trade—were not solely feats of ingenuity but also feats of endurance in the face of dangerous environments.

Conclusion

As researchers continue to analyze the CT data and anatomical details, the Chilean mummy stands as a powerful testament to the realities of ancient turquoise mining. The combination of precise imaging and careful excavation allows us to piece together a tragedy that occurred a millennium ago, offering a clearer view of how people in this region lived, worked, and faced peril beneath the earth.