Introduction: Europa’s Ocean World

Long considered one of the most promising places to search for extraterrestrial life, Jupiter’s moon Europa is an ice-covered world believed to cradle a vast ocean beneath its rigid shell. The seafloor, far from being barren, could hold clues about the chemical energy and environmental conditions that sustain life, or it might be an abyss of quiet, lifeless waters. Scientists are unraveling what Europa’s seafloor can tell us about habitability, hydrothermal activity, and the limits of life in our solar system.

The Case for a Subsurface Ocean

Observations from spacecraft and telescopes have painted a compelling picture: Europa likely hosts a global ocean, salted and salty enough to conduct electrical currents and support chemical reactions. The ice shell above this ocean is estimated to be a few to tens of kilometers thick in places, acting as both a barrier and a gateway. If warm pockets exist near the seafloor, they could drive circulation, delivering energy and nutrients to potential microbial ecosystems. The seafloor becomes the interface where ocean chemistry and geology meet, making it a prime target in the search for life beyond Earth.

What the Seafloor Could Tell Us

The seafloor of Europa is not simply a static plane of rocks; it is an active, dynamic boundary that could host hydrothermal-like systems or mineral deposits formed by interactions between water and Europa’s rocky interior. Any life would rely on chemical energy rather than sunlight, possibly through chemosynthesis at vents or near mineral-rich plumes. Researchers look for signs such as mineral plumes rising through the ice, complex rock-water interactions, and anomalies in ice crust strain that might indicate underlying activity. Even in a seemingly quiet environment, tiny energy fluxes could sustain microbial life for eons.

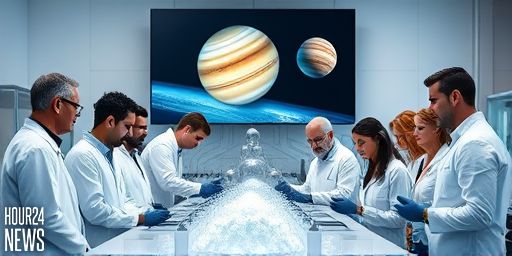

Energy, Chemistry, and Habitability

Life as we know it requires energy and a stable chemical source. Europa’s seafloor could provide both through water-rock interactions, radiolytic chemistry from Jupiter’s radiation belt, and possible hydrothermal-like systems. Radiolysis—where radiation splits water molecules to produce hydrogen—could fuel microbial ecosystems and support a larger biosphere than previously imagined. Scientists assess the redox gradients, salt chemistry, and mineralogy on the seafloor to estimate how hospitable the environment might be for living organisms.

Evidence from Plumes and Surface Features

Plume activity observed at Europa’s surface offers a tantalizing link to an active ocean beneath. If plumes vent material from the seafloor into space, future missions could sample ocean-derived compounds without drilling through kilometers of ice. Even without direct plume detection, surface fractures and chaos terrains hint at exchange processes between the ocean and the ice shell. Each fragment of data helps refine models of what lies beneath and how energy and nutrients might reach any potential life forms at the seafloor.

Mission Prospects: Probing the Seafloor

NASA’s Europa Clipper, alongside potential future landers and ice-penetrating missions, aims to characterize the ice shell’s thickness, assess ocean chemistry, and search for surface features that reveal seafloor processes. A future lander or submarine could directly sample the subsurface ocean or analyze plumes for biosignatures. The challenges are immense—cold temperatures, radiation exposure, and thick ice require robust technology—but the potential rewards are equally profound, offering insights into habitable environments beyond Earth’s cradle.

Why It Matters

The question of whether Europa’s seafloor harbors life touches on fundamental issues in astrobiology and planetary science. If life exists, Europa expands the range of habitable worlds and informs our understanding of how life begins and persists in extreme environments. Even if the seafloor remains lifeless, studying its chemistry and geology will illuminate the diversity of planetary oceans in our solar system and guide the search for life elsewhere in the universe.