Introduction

Conservationist Margaret Jacobsohn has sparked a heated debate about who should lead the fight against the illegal ivory trade. In the wake of a recent decision at the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), she argued that Western animal rights groups and conservation models may not be the most effective path to safeguarding African wildlife. Instead, she emphasized the crucial role of empowering local communities living closest to Africa’s elephants and other vulnerable species.

Why the Ivory Trade Debate Matters

The global ivory trade has long been a flashpoint in conservation circles. While bans and regulations exist in many countries, illicit markets persist, driven by demand in parts of Asia and elsewhere. Critics contend that top-down strategies, often led by international NGOs, can overlook the social and economic realities of communities who bear the consequences of such trade. Proponents of community-centered conservation argue that sustainable protection depends on local incentives, traditional knowledge, and direct participation in enforcement and monitoring.

Margaret Jacobsohn’s Perspective

Speaking to reporters and stakeholders last week, Jacobsohn underscored a shift in thinking about where responsibility for conservation should rest. “African wildlife will not be protected through Western conservation approaches alone,” she said. “The involvement of local communities is not just beneficial—it’s essential.”

Jacobsohn noted that communities living adjacent to elephant ranges often face daily challenges, including man-elephant conflict, crop raiding, and economic pressure from poaching networks. In her view, any durable safeguard against the illegal ivory market must align the interests of these communities with the health of wildlife populations. Without their buy-in, she warned, policies risk becoming well-intentioned but ineffective.

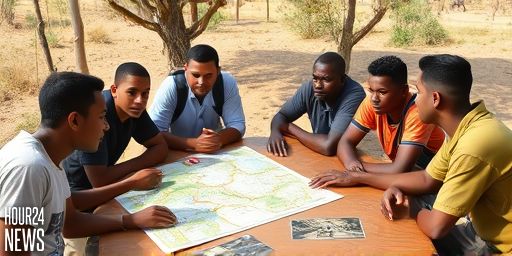

Community-Centered Conservation in Practice

- Co-management of Wildlife Lands: Local groups partner with governments to manage parks and reserves, ensuring patrols, reporting systems, and revenue-sharing models that benefit residents.

- Alternative Livelihoods: Programs that provide sustainable income—such as eco-tourism, beekeeping, or craft markets—create economic reasons to protect wildlife rather than exploit it.

- Traditional Knowledge: Indigenous and rural communities often possess nuanced understanding of animal behavior and seasonal patterns that can improve anti-poaching efforts and habitat management.

- Community-led Monitoring: Local stewards, equipped with training and tools, can document poaching incidents, track trends, and collaborate with authorities more effectively than distant actors.

The Role of CITES in the Debate

CITES decisions have long shaped international trade in endangered species. The most recent discussions—whether to tighten controls or embargo certain ivory flows—are deeply symbolic as well as practical. Jacobsohn argues that the effectiveness of any CITES mandate will depend on how well it aligns with on-the-ground realities in African ecosystems. If local communities view measures as protecting their interests and livelihoods, compliance and enforcement are more likely to follow.

Balancing Global and Local Interests

The debate is not about dismissing global responsibility. Rather, it is about recalibrating the balance between international oversight and local sovereignty. Western groups have played a pivotal role in funding anti-poaching units, scientific research, and capacity-building. Yet, Jacobsohn’s critique invites a broader coalition—one that places local leaders and community organizations at the helm, with Western partners offering support that respects local governance structures.

Implications for Policy and Action

If policymakers take Jacobsohn’s recommendations seriously, a new paradigm for conservation could emerge—one that treats local communities as equal stewards of biodiversity and beneficiaries of conservation outcomes. This approach would require transparent benefit-sharing mechanisms, robust anti-corruption safeguards, and sustained investment in community-led enforcement, education, and habitat restoration.

For conservationists, NGOs, donors, and governments, the path forward may involve listening more, subsidizing locally led initiatives, and reframing success metrics beyond arrests and bans. The ultimate measure would be healthier elephant populations, resilient habitats, and communities that are financially and morally invested in preservation.

Conclusion

Margaret Jacobsohn’s call to center local communities in the fight against the ivory trade reflects a broader shift in global conservation discourse. If Africa’s wildlife is to endure in the face of growing pressures, the region’s own people must be the primary beneficiaries and drivers of protection. Western groups can support, but the cornerstone must be community-led action, integrated with fair policy frameworks and sustained international collaboration.