Introduction: Wealth, Security, and Metals in the Ancient World

From antiquity to early imperial eras, precious metals were more than decorative objects. They acted as durable stores of value, systems of exchange, and strategic tools for wealth management. In a society where credit markets were rudimentary and coinage varied by region, metals like gold, silver, and copper served as the backbone of economic life. The article drawn from Dr. Konstantine Panegyres’s research in The Conversation traces how civilizations invested in these metals to weather risk, fund public projects, or reward loyalty.

Why Metals Were Preferred: Intrinsic Value and Universal Acceptance

Gold and silver were prized for their rarity, malleability, and enduring luster. Unlike grain or livestock, metals do not quickly spoil, making them ideal for long‑term savings. The consistent weight and fineness of minted coins enabled traders across vast distances to agree on value, reducing the friction of exchange. Copper and its alloys, while not as valuable per unit, formed everyday currency and facilitated routine transactions, extorting the metal’s role as a practical anchor in urban and rural economies alike.

Ways the Ancients Invested in Metals

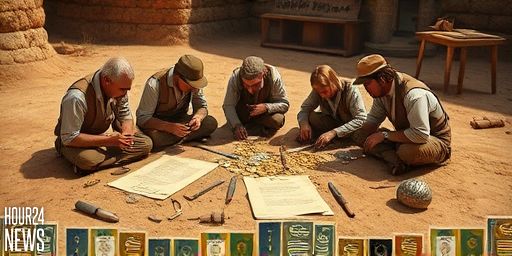

Minted Coins and Hoards

Coins were the most visible manifestation of metal investment. Rulers and city-states minted gold, silver, and bronze coins to pay troops, finance infrastructure, and stabilize markets. Private citizens amassed hoards as a hedge against famine, war, or political upheaval. Archaeological finds reveal secure vaults beneath temples or palaces where individuals stored wealth in metal, often pairing coins with precious metals in weight-based thrift. Hoarding served both personal security and a signal of financial resilience in uncertain times.

Symbolic and Religious Deposits

Beyond market uses, metals had symbolic value. Temples and sanctuaries often held deposits of gold and silver earned through offerings or donations. These deposits could be liquidated in emergencies or used to fund religious festivals and public works. In some cultures, the moral economy of wealth included the obligation to care for orphans, widows, or the poor—mechanisms often backed by metal reserves that could be drawn down in crisis.

Raw Metals and Commodities Markets

Not all investment was about coins. Raw gold, silver, and copper were traded as bullion or ingots in and between mining regions. Traders would ship bullion along caravan routes or via early ports, sometimes with standardized weights, sometimes in more informal packets. The extraction and control of mines—whether gold in Anatolia, silver in the Iberian world, or copper in Cyprus and the British Isles—directly affected metal supply and, by extension, investment opportunities and prices.

Domestic Use as a Form of Wealth Protection

Households sometimes melted coins for jewelry, religious artifacts, or domestic tools, turning wealth into portable assets for family security. This conversion—metal into objects of utility or display—was a pragmatic response to inflationary pressures, political risk, or social disruption. In effect, households used metal both as a form of cash and as a material stored wealth that could be re-monetized when needed.

Risk, Diversification, and Public Finance

Investors in the ancient world faced similar risks to modern savers: policy changes, war, debasement of coinage, and natural disasters. Diversification across metals, coin systems, and forms of wealth—coins, bullion, and storage in temples or treasuries— helped spread risk. States also used metals strategically, issuing coinage with stable weight standards to support commerce and public finance. Debasement, a common tool to fund wars, illustrates the delicate balance between revenue needs and the long‑term value of metal‑backed money.

Legacy for Modern Investors

What can contemporary readers learn from ancient metal investment? First, metals offered a portable and durable form of wealth that could adapt to political and economic shocks. Second, the mix of coins, bullion, and institutional deposits shows that diversification—across different metals and storage forms—remains a timeless principle. Finally, the social and religious aspects of metal wealth remind us that value is not purely financial; trust, legitimacy, and communal institutions influence how wealth is stored and transferred across generations.

Conclusion

The ancients invested in precious metals not merely for aesthetic appeal but as fundamental instruments of security, exchange, and public finance. By examining coinage, hoards, temple deposits, and mining, we gain a clearer understanding of how metals shaped risk management and wealth preservation long before modern financial instruments existed. Dr Konstantine Panegyres’s exploration illuminates how these practices echo through time, offering enduring lessons for today’s investors seeking resilience in a volatile world.