Introduction: A Possible Earliest Human Ancestor

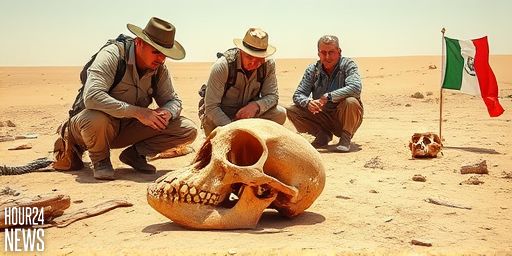

The discovery of Sahelanthropus tchadensis, a seven-million-year-old ape, has reignited the debate over what marks the dawn of humanity. Found in Chad and first described in 2002, this fossil remains one of the most provocative candidates for the earliest human ancestor. Scientists debate whether its skull and skeletal remains reveal an ancestor who walked upright two million years earlier than most hominids, potentially reshaping our timeline of human evolution.

What the Fossil Tells Us About Bipedalism

Central to the discussion is the specimen’s potential locomotor capacity. Some researchers argue that certain features of Sahelanthropus tchadensis, including the orientation of the foramen magnum—the hole where the spinal cord enters the skull—hint at a more upright posture than typical great apes. If these interpretations hold, Sahelanthropus could represent an early phase of bipedalism, a key trait that characterizes later human lineages.

However, others caution that interpreting a single skull and fragmentary remains is risky. They point out that cranial and dental features may reflect a diverse range of locomotor styles in forested or mixed environments, and may not conclusively prove habitual upright walking. The scientific community continues to scrutinize the fossil against other early hominid candidates to avoid over-connecting limited evidence with a grand evolutionary conclusion.

Why This Discovery Matters for Evolutionary Timelines

If Sahelanthropus tchadensis did walk upright more than two million years earlier than other known hominids, the emergence of bipedalism could have occurred sooner than once thought. Bipedal locomotion is a foundational step in human evolution, enabling freed hands for tool use, transportation across open landscapes, and later, complex cognitive developments. A seven-million-year-old upright-walking ancestor would push back the origins of this trait and prompt re-evaluations of how climate, habitat shifts, and geography influenced early human lineages in Africa and beyond.

Context: Where and How We Study Early Hominids

Sahelanthropus tchadensis was discovered at site sites in Chad that preserve ancient sedimentary layers. Fossil finds like this are painstakingly analyzed with comparative anatomy, measurements, and, when possible, dating techniques such as radiometric methods. In addition to the skull, paleontologists examine tooth wear, jaw structure, and other skeletal remnants to piece together lifestyle, diet, and movement. The interpretation often relies on comparing Sahelanthropus to both earlier ape-like species and later, more clearly human relatives.

Current Debates and Future Research

The scientific conversation around Sahelanthropus tchadensis remains dynamic. Some researchers maintain a cautious stance, emphasizing that a solid case for early bipedalism requires more complete fossils and corroborating evidence from the surrounding geology. Ongoing fieldwork in Chad, along with discoveries at other sites across Africa, aims to fill gaps in the fossil record. Advances in imaging and analysis may reveal subtler anatomical clues, helping to distinguish true bipedal adaptations from convergent traits that arose in different lineages.

Conclusion: A Landmark, Yet Contested, Piece of Human History

Sahelanthropus tchadensis stands as a landmark in the story of human origins, representing both a milestone and a source of debate. Whether it truly is the earliest human ancestor hinges on future discoveries and refined methods. What remains clear is that the path to humanity is not a straight line but a complex web of adaptations, environments, and migrations that began long before our species appeared.