New clues emerge in the murky dawn of human evolution

The search for the earliest ancestor of humankind has long read like a saga of partial clues and stubborn debates. New bone analyses have reignited the conversation, suggesting a more nuanced story of how our predecessors first left the ground-and how they went from moving on all fours to standing tall. While these findings are exciting, they also raise fresh questions about timing, anatomy, and the environmental pressures that pushed early hominins toward bipedalism.

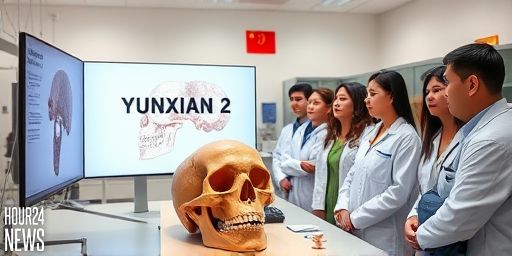

What the new bone analysis shows

Researchers examining recently discovered skeletal fragments have used advanced imaging and comparative anatomy to infer how these early beings bore weight, balanced their bodies, and spread their limbs during movement. Some bones appear to indicate a transitional form, one that could stand upright for short periods or on uneven terrain without sacrificing stability. In particular, wear patterns on joints and the shape of the pelvis and femur are interpreted as signs of emerging bipedality rather than a fully modern gait.

Crucially, the latest work does not claim a single moment when humanity suddenly stood up. Rather, it paints a mosaic: multiple populations may have experimented with upright locomotion at different times and in different places. This view aligns with how the fossil record typically unfolds—fragmentary, regionally diverse, and shaped by environmental shifts that opened new ecological niches.

Why these bones matter for the big picture

Any credible argument for a pivotal human trait, such as bipedalism, hinges on morphology that can be linked to practical function. The pelvis, spine, and leg bones are central to understanding weight transfer and balance. Fresh analyses are increasingly cautious about assigning a precise date to when upright walking became the dominant mode of locomotion.

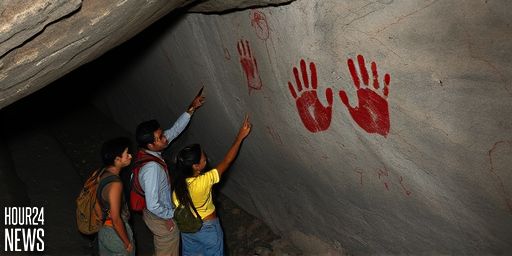

The emerging perspective emphasizes gradual change rather than a single leap. This has broad implications for how we interpret other markers of early hominin behavior, including tool use, social organization, and ecosystem foraging strategies. If upright walking developed piecemeal, then shifts in climate and landscape likely played a decisive role in driving that evolution forward.

Debates and caveats that accompany new evidence

Scientists remain careful about overreading limited specimens. A few bones can suggest tendencies but rarely confirm a definitive ancestral blueprint. Critics warn against anchoring broad evolutionary theories to a small number of fossils or to particular anatomical interpretations that may reflect variation within a species rather than a new species trait. Moreover, dating methods carry uncertainties that can blur the timeline of when bipedalism first appeared in different lineages.

In this light, the fresh bone analyses contribute to a dynamic conversation rather than a final consensus. They encourage a more pluralistic view of early human evolution, one that accommodates parallel experiments in form and function across geographies. The challenge for researchers is to assemble a coherent picture that reconciles anatomy with the ecological context in which these early hominins lived.

What lies ahead for the study of our first steps

Future discoveries, improved dating techniques, and more complete skeletons will be crucial. Each new fossil has the potential to nudge the field toward a clearer narrative of when, where, and why upright walking evolved. In the meantime, the current findings remind us that the story of humankind is not a straight line but a branching, intricate history shaped by adaptation, environment, and chance.

Why this matters to our understanding of humanity

Beyond curiosity, tracing the origins of bipedalism sharpens our understanding of human biology and variability. It informs how early humans navigated diverse landscapes, exploited resources, and interacted with other hominin groups. As researchers piece together the evidence, the portrait of our distant ancestors becomes more textured—and more fascinating—to study, debate, and learn from.