Introduction: A call for thoughtful constitutional refinement

Since the 2010 Constitution, Kenya has made notable progress in governance, citizen participation, and the decentralization of power. Yet the journey toward a more robust democracy is ongoing. The drive to reach the 2027 political milestones should not eclipse the imperative to refine the constitutional framework in a deliberate, inclusive manner. Quick fixes risk undermining the gains already achieved and could sow doubt about the legitimacy of future reforms.

Why haste risks undermining democracy

Constitutional changes can reshape the balance between the executive, legislature, and judiciary. When reform processes are rushed, there is a danger of muddying accountability, creating ambiguities, and inviting constitutional contests that drain political energy rather than deepen democratic norms. A well-ordered review, anchored in broad stakeholder consultation, can strengthen the social contract rather than fracture it. Kenya’s path to 2027 should be about durable tweaks, not hurried upheavals.

What refinement should look like in practice

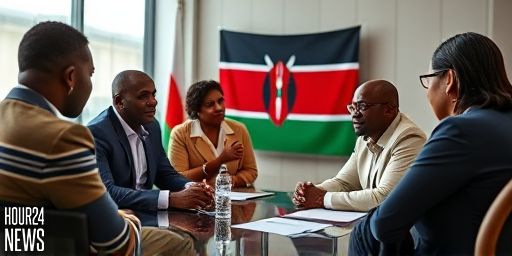

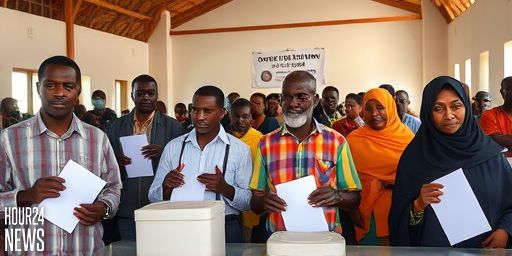

Inclusive process: A genuine national conversation must involve parliament, county assemblies, civil society, professional associations, and marginalized voices. A transparent mechanism with clear timelines, published options, and public input channels can diffuse skepticism and build legitimacy.

Clear subsidiarity and devolution: The constitution already enshrines devolution; refining it should focus on the practicalities of resource allocation, accountability at the county level, and safeguards against power grabs. Ensuring that counties can innovate while maintaining national cohesion is essential for wananchi—ordinary citizens—to feel the benefits of governance at home.

Judicial independence and clarity of roles: A durable constitution should delineate the lines between institutions, specify appointment processes, and safeguard judicial independence. When reforms are ambiguous on jurisdiction or oversight, tribunals and legal challenges proliferate, delaying development projects and eroding public trust.

Rights protection with enforceable remedies: The constitutional framework must translate rights into effective remedies. Constitutional guarantees are only as strong as the courts’ ability to enforce them and the public’s awareness of their rights.

Economic and social implications

Constitutional changes do not exist in a vacuum. They affect investment climate, public service delivery, and the social contract with the Kenyan people. Dry legalese without practical consequences can alienate citizens; conversely, well-constructed amendments can accelerate service delivery, improve accountability in public spending, and bolster citizen trust in government institutions.

A roadmap for 2027, with patience as a virtue

The objective should be a refined constitution that is less prone to post-implementation constitutional wrangles and more adaptable to Kenya’s evolving needs. A staged approach—pilot reforms in select sectors, evaluate outcomes, and scale—allows for learning and adjustment. Such a strategy minimizes disruption to ongoing governance and ensures that reforms translate into tangible improvements for the people.

Conclusion: Steady reform to sustain gains

Kenya’s democracy has matured through citizen participation, decentralization, and institutional checks. Rather than a rushed march toward 2027, the country deserves a measured, inclusive constitutional refinement that builds on progress and strengthens the social contract. The aim should be clarity, accountability, and enduring legitimacy—hallmarks of a resilient democracy that serves wananchi for generations to come.