New Clues from a Belgian Cave

A recent study examining remains from a Belgian cave has revived a controversial topic in human evolution: the possibility that Neanderthals practiced cannibalism, including the killing and eating of infants or very young children. The research focuses on bones recovered from a site where evidence of cannibalism had previously been identified, but new analyses reveal surprising details about the victims and the context of the deaths.

Who Were the Victims?

Scientists analyzing the fractures, tooth marks, and cut marks on the bones concluded that the victims were not a random group of individuals. The assemblage includes children and young women, suggesting a selective pattern rather than indiscriminate scavenging. While this does not definitively prove ritual cannibalism, it strengthens the case that Neanderthals may have engaged in anthropophagy for nutritional or cultural reasons in this locale and at this time period.

What the Evidence Reveals

Key indicators in the bones include cut marks consistent with marrow extraction, breakage patterns typical of butchery, and sporadic signs of meat removal. In some specimens, researchers detected delicate modifications that could indicate careful processing of body parts beyond mere scavenging. The careful work of modern laboratories—microscopy, isotopic analysis, and comparative anatomy—helps distinguish Neanderthal cannibalism from other forms of bone modification, such as predation by large carnivores or accidental breakage.

Why the Findings Matter

Whether these acts were common or sporadic, the possibility that Neanderthals consumed members of their own groups offers a window into the stresses and survival strategies of late Pleistocene humans. It challenges a simplistic view of Neanderthals as exclusively “other” to modern humans and invites broader discussion about family structure, conflict, and subsistence in ancient communities. The Belgian site adds a new data point to a global debate about anthropophagy among our extinct cousins and its potential motivations—nutrition, ritual practice, or social consequence.

Interpreting Neanderthal Behavior

Scholars caution against drawing sweeping conclusions from a single site. Neanderthals lived in diverse environments across Europe and western Asia, and their practices likely varied widely by group, season, and resource availability. The Belgian findings stimulate new lines of inquiry: Were such acts opportunistic or culturally ingrained? Did family units or neighboring groups participate in cannibalism, and under what ecological pressures? As researchers compare this site with others around the world, the broader narrative of Neanderthal life becomes increasingly nuanced.

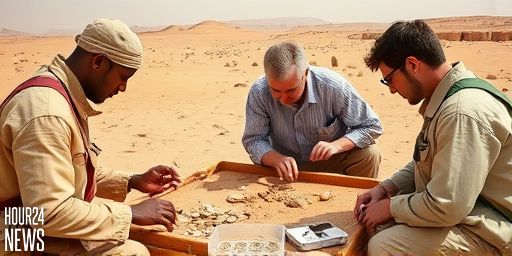

Methodology and Future Research

The study employs a combination of morphological assessment and modern dating techniques to place the remains within a clear temporal framework. Radiocarbon dating, isotopic analysis, and 3D imaging enable scientists to reconstruct how these individuals might have lived—and how they died—within a harsh Pleistocene landscape. Ongoing work aims to map patterns across additional sites to determine whether the Belgian case is an exception or indicative of a wider practice among Neanderthal populations.

Public and Scientific Response

News of potential Neanderthal cannibalism tends to provoke strong reactions, underscoring ongoing interest in human origins and the complexities of prehistoric life. The current findings are being discussed in scholarly circles and in public-facing outlets, highlighting the importance of careful interpretation and ongoing discovery as more bones and sites come into view. Whatever the final consensus, the research enriches our understanding of Neanderthals and the diverse strategies they employed to survive in challenging environments.

Conclusion

While no single study can resolve all questions about Neanderthal cannibalism, the Belgian cave evidence contributes a provocative piece to the puzzle. If future discoveries corroborate these patterns, our view of Neanderthal society may expand to include more complex and varied behaviors, revealing a species that adapted to scarcity with facets that resemble both survivalist pragmatism and social complexity.