Unraveling a Case that Still Haunts Paleontology

The Tendaguru Quarry in present-day Tanzania is not just a fossil-rich site; it is a lens into the tangled web of science, empire, and memory. This article continues the examination started in Whose Dinosaur? The Colonial Legacy Keeping Tanzania’s Fossils in Berlin, tracing how real history often sits at the intersection of discovery, ownership, and interpretation. At stake is more than a single dinosaur specimen; it is a question about responsibility, representation, and whether complexity can ever excuse overlooked harms in scientific practice.

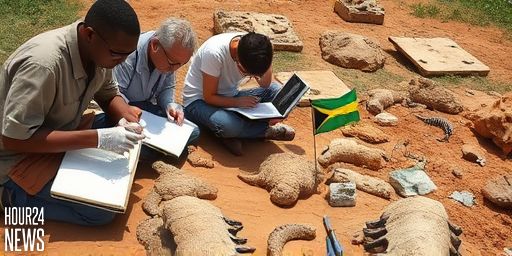

The Tendaguru Narrative: Discovery, Extraction, and the Weight of Legacy

Between 1909 and 1913, German expeditions yielded some of the era’s most complete sauropod fossils. The scientific achievements were substantial, but the process was inseparable from the colonial context in which it unfolded. Fossil beds that had nurtured life for millions of years became a stage for researchers, patrons, and administrators who mapped power as deftly as they mapped bones. In Tanzania, the Tendaguru story reverberates beyond the bones themselves: it is a meditation on who gets to interpret the past, who benefits from it, and who remains unheard in the recounting.

Complexity, Power, and Responsibility

Proponents of examining colonial legacies argue that complexity should not shield accountability. The unpacking of Tendaguru’s history reveals how scientific prestige often traveled hand in hand with political authority. The excavation produced a cascade of scientific papers, vintage photographs, and institutional collaborations that, in hindsight, require careful ethical appraisal. Critics assert that reductionist narratives—good science, bad politicians—obscure ongoing harms: unequal access to the fossils, the long-running debates over repatriation, and the reframing of local scientific agency in Tanzania.

What the Fossils Tell Us Now

Today, the Tendaguru fossils sit as a perpetual reminder that the past is a contested space. Museums in Berlin and other European capitals hold pieces of the Tendaguru collection, while Tanzanian researchers and curators seek greater access, visibility, and control. This shift from possession to partnership is not merely a diplomatic gesture but a redefinition of how palaeontological value is created and shared. The field increasingly recognizes that scientific breakthroughs gain depth when accompanied by equitable collaboration, transparent provenance, and robust local involvement.

Reparative Paths and the Future of Fossil Stewardship

Reconciliation in this context means more than returning bones; it means reforming how institutions describe, display, and benefit from fragile heritage. Several museums have begun formal dialogues about loan agreements, co-curation, and capacity-building programs that empower Tanzanian museums and universities. The Tendaguru case becomes a blueprint for how to navigate complex legacies without erasing the achievements—both scientific and cultural—that the fossils symbolize.

Conclusion: Complexity as a Tool, Not an Excuse

Is complexity an alibi for neglecting ethical considerations, or can it illuminate a more honest, inclusive approach to history? The Tendaguru dinosaur case suggests the latter. It invites paleontologists, historians, and policymakers to acknowledge past missteps while laying out practical steps toward shared stewardship. In asking who owns the story of Tendaguru, we must also ask who gains from its telling—and who is left out. The unresolved questions are not a denial of scientific worth; they are a call to stewardship that respects both the bones and the communities that carry their memory.