Introduction: Recalling a Case That Haunts Paleontology

The Tendaguru Dinosaur excavations in the early 20th century have long stood as a touchstone for debates about science, empire, and ownership. A follow-up to our previous report on the colonial conditions that kept Tanzania’s fossils in Berlin, this article digs deeper into the question: is complexity merely an excuse used to dodge accountability for historical and ethical oversights? The answer, as with many long-running archival puzzles, is not simple, but the stakes are real for scientists, national heritage, and publics seeking transparent storytelling about the past.

The Historical Terrain: Excavations, Extractive Practices, and Rhetoric

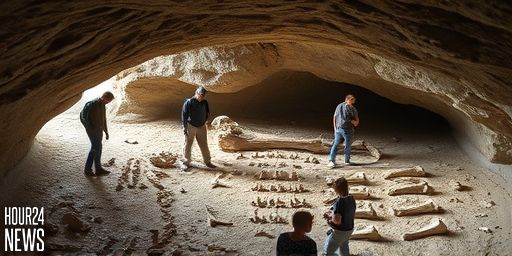

During the Tendaguru expeditions of the German colonial era, a wealth of dinosaur specimens were collected and shipped to European institutions. Critics argue that the scale of extraction, the lack of local control, and the framing of science as a universal good often masked unequal power relations. Supporters contend that the discoveries advanced paleontology in ways that wouldn’t have happened otherwise. What remains undeniable is that the bones emerged from a complex colonial context in which legality, access, and knowledge production were intertwined with a broader project of empire.

The Role of Narrative Complexity

In contemporary discussions, complexity is sometimes invoked to shield institutions from addressing difficult questions about restitution, access, and credit. By foregrounding technical debates over display, preservation, and curation, museums and researchers can sidestep debates about who should own the fossils and who deserves to tell their story. Yet complexity also reflects genuine scholarly nuance: multiple institutions, long chains of custody, and shifting standards for ethical stewardship. The challenge is to separate legitimate epistemic caution from evasive rhetoric that delays accountability.

What Accountability Looks Like Today

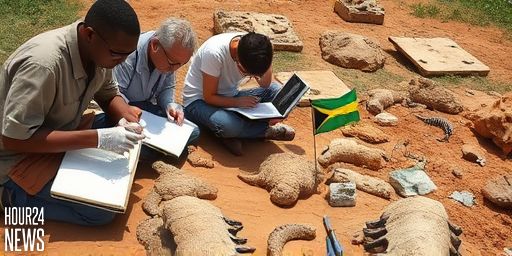

Several strands of reform are visible in modern paleontology and museum practice. First, provenance documentation has become more robust, with clearer records of where specimens were found, how they were treated, and the different institutions involved in their study. Second, there is growing advocacy for equitable partnerships that involve local scientists, educators, and communities in decision-making about collection, display, and repatriation. Third, open-access scholarship and public-facing provenance research help demystify the chain of custody, making it harder for expediency to mask ethical gaps.

Repatriation and Shared Stewardship

Repatriation debates mirror broader conversations about decolonizing science. Returning artifacts or sharing stewardship with source countries can recalibrate power dynamics and enrich local scientific capacity. However, practitioners warn that successful partnerships require sustained investment, transparent governance, and mutual respect for different cultural and scientific values. Tendaguru serves as a focal point for these conversations, illustrating how restitution is not a single act but an ongoing process of negotiation and collaboration.

How the Tendaguru Case Informs Current Science Policy

Policy-makers, scholars, and museum leaders can draw several lessons from Tendaguru: the necessity of robust provenance, the importance of inclusive governance, and the risk of using complexity as a shield. A modern approach treats historical culpability as a living matter—one that shapes curatorial practice, funding decisions, and public trust. For Tanzania and other nations with contested colonial legacies, the case underscores the value of national frameworks for heritage management and international partnerships grounded in reciprocity.

Conclusion: Complexity as a Mirror, Not a Mask

Is complexity merely an excuse? The Tendaguru dilemma suggests that it can be both a genuine scholarly constraint and a convenient cover for past missteps. The unresolved issues surrounding the fossils demand continued scrutiny, more transparent documentation, and a commitment to co-creating narratives with the people and institutions most connected to Tendaguru’s legacy. By embracing constructive complexity—while resisting rhetorical evasions—paleontology can honor both intellectual rigor and ethical accountability.