Introduction: A Window into Neanderthal Mobility

A recent discovery from Crimea is reshaping our understanding of Neanderthal migration. When researchers analyzed a tiny bone fragment, they uncovered DNA that bridges Neanderthals from this Black Sea region with populations as far away as Siberia. The finding adds a new chapter to the story of how ancient communities moved across Eurasia, suggesting that Neanderthals may have traveled longer distances and established broader networks than previously believed.

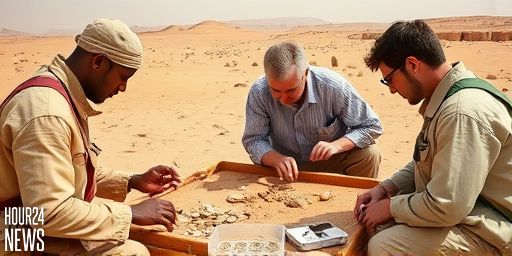

The Discovery: A Tiny Bone, a Big Pattern

In a carefully controlled laboratory setting, scientists extracted ancient DNA from a small bone fragment unearthed in Crimea. The genetic material showed a surprising level of similarity to Neanderthal DNA found in Siberian specimens, despite the great geographic distance that separates the two regions. This pattern hints at a connected habit of movement, trade routes, or repeated migrations that linked disparate Neanderthal groups.

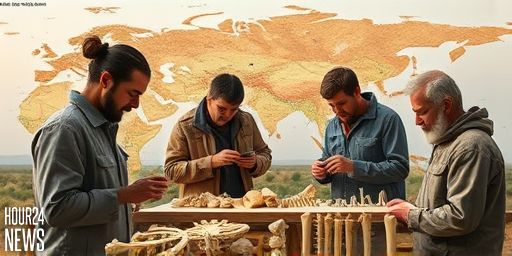

What the DNA Tells Us About Migration

Until now, Neanderthal migration research often painted a patchwork map: pockets of related populations with limited signals of interaction over vast tracts of Eurasia. The Crimea finding challenges that view. By comparing the Crimean fragment to Siberian genomes, researchers detected shared genetic markers that imply either direct travel by individuals or sustained contact through intermediary groups. Either scenario points to a more dynamic Neanderthal network spanning thousands of kilometers.

Implications for Eurasian Prehistory

The implications extend beyond Crimea and Siberia. If Neanderthals routinely moved across large distances, their interactions with early Homo sapiens and other hominin groups could have been more frequent and complex than previously thought. These connections might have influenced technology transfer, subsistence strategies, and even patterns of adaptation to diverse environments across ice-age Eurasia.

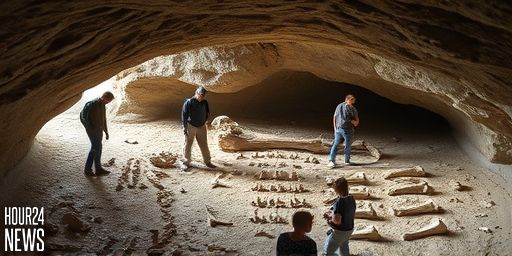

Why Crimea Matters

Crimea’s fossil record has yielded crucial clues about Neanderthal life, climate, and movement. The new DNA link from a tiny bone fragment demonstrates that even seemingly isolated regions were part of a broader network. This supports a growing view of Neanderthals as adaptable, mobile populations capable of navigating challenging landscapes—from steppes to mountain passes—over tens of millennia.

What Comes Next in Neanderthal Research

Experts caution that a single fragment can illuminate but not definitively map ancient migrations. The next steps involve locating more human and hominin remains across Eurasia, sequencing their DNA, and building a more complete network of Neanderthal connectivity. Advances in ancient DNA techniques will continue to refine our understanding of how these populations lived, moved, and interacted with the changing climate of the last 50,000 years.

Conclusion: A Connected Past

The Crimea DNA discovery reinforces a broader narrative: Neanderthals were part of a geographically expansive and interconnected prehistoric world. Far from isolated groups, they appear to have left genetic trails across Eurasia, underscoring the complexity and resilience of our closest ancient relatives. As researchers gather more evidence, the map of Neanderthal life will become clearer—and perhaps more surprising—than ever before.