Understanding a Silent Crisis

For many women, childbirth should be a moment of hope and new life. Yet for thousands, it becomes a painful battle with obstetric fistula, a hole between the birth canal and bladder or rectum that causes incontinence. The result is not only physical suffering but isolation, stigma, and the loss of social and economic opportunities. In places with limited access to safe cesarean sections and emergency obstetric care, the condition remains a hidden wound that echoes through generations.

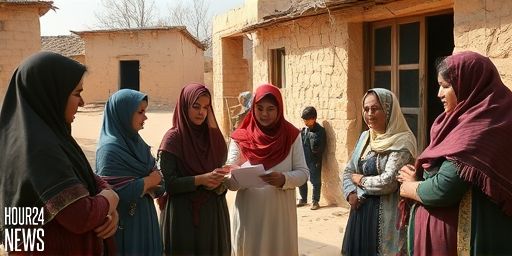

Farhiya’s Story: From Isolation to Empowerment

Farhiya, a 38-year-old mother from rural Beletweyne, faced a life-altering ordeal. After a difficult labor, she developed a fistula and the relentless leakage that followed. The shame and fear of judgment kept her at the margins—physically uncomfortable and emotionally strained, she felt cut off from her community. She describes the weight of being constantly stressed, unable to participate in village life, and doubting her future as a mother. Her story is not unique; it is a stark reminder that childbirth can threaten a woman’s dignity as much as her health.

What Causes Obstetric Fistula?

Obstetric fistula typically arises from prolonged obstructed labor without timely access to surgical intervention. When a baby’s head is too large or the labor is not monitored, the pressure can cut off blood flow to the tissues inside the birth canal. This damage creates a hole through which urine or stool leaks, leading to incontinence. Beyond the physical ailment, the condition often stems from systemic gaps in prenatal care, transportation barriers, and cultural stigmas that discourage seeking help early.

Healing Is Possible: Medical and Social Pathways

Experts emphasize that obstetric fistula is treatable with surgery, usually a repair that closes the hole and restores continence. Recovery depends on the individual’s health, the fistula type, and the availability of post-operative care. But healing goes beyond the operating room. Comprehensive care includes:

- Accessible, skilled obstetric surgical services to perform fistula repairs.

- Pre- and post-operative counseling to address mental health, stigma, and self-esteem.

- Rehabilitation programs that support reintegration, including education and income-generating activities.

- Prevention efforts focused on timely labor monitoring, emergency obstetric care, and family planning options.

The Role of Communities and Health Systems

Community acceptance and health system strengthening are essential. When communities understand fistula as a medical condition—not a personal failing—women feel safer seeking care. Health facilities need trained surgeons, functional referral networks, and affordable services. Governments, NGOs, and local leaders can collaborate to remove financial barriers, transport hurdles, and stigma, ensuring women like Farhiya can access life-changing surgery and follow-up care.

A Call to Action: Support and Solutions

Ending the hidden wounds of childbirth requires a multi-pronged approach. Public health campaigns should highlight fistula as preventable and curable, encouraging early care-seeking. Investment in maternal health infrastructure, including mobile clinics and surgical camps, can reach remote communities. Peer support groups empower survivors to share experiences, rebuild confidence, and advocate for safer birth practices. Each repaired fistula is a step toward rebuilding a life—pain relieved, dignity restored, and a woman’s voice amplified in her community.

Hope for the Future

Farhiya’s journey toward healing demonstrates the resilience of women facing obstetric fistula. With access to surgery and supportive networks, she began a new chapter—participating in community life, reconnecting with her family, and pursuing education and small-scale work. Her story, echoed across regions with similar challenges, is a powerful reminder that ending the stigma and delivering real care can transform lives—one patient, one community, one country at a time.