Introduction: A mission in the Sahara

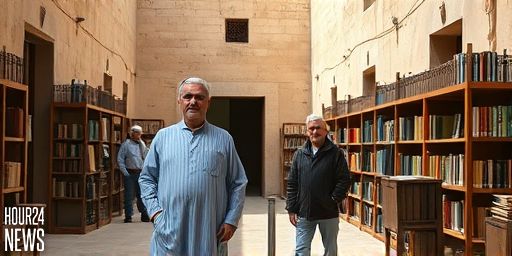

On a quiet afternoon in the desert town of Chinguetti, Mauritania, 67-year-old Saif Islam steps into the courtyard of a library that has stood for centuries. Clad in a flowing boubou striped in two shades of blue, he moves with a deliberate, if unsteady, pace toward a stubborn enemy: shifting desert sands that threaten to bury a city’s memory. His work mirrors a broader effort to safeguard Mauritania’s cultural heritage as climate and time push against fragile archives stored in earthen walls and palm-thatched roofs.

Chinguetti: The city that holds centuries of memory

Chinguetti, often called a “city of libraries,” rose along ancient caravan routes, gathering manuscripts and texts from across West Africa. Its libraries—many centuries old—are repositories of Islamic scholarship, astronomy, jurisprudence, poetry, and local history. The town’s streets wind between mud-brick houses, with towers and minarets that cast long shadows across the desert. Yet the sands are a relentless force here, moving with the wind and gradually shifting the shoreline of memory. In this setting, preservation is as much a daily struggle as a scholarly pursuit.

Saif Islam’s role: caretaker, custodian, and advocate

For years, Saif Islam has walked the fine line between preservationist and activist. The library courtyards where he stands are not merely houses of books; they are living classrooms where elders translate forgotten texts and children discover the glow of a well-worn page under a dwindling lamp. The public face of a quiet movement, Islam teaches how to catalog fragile manuscripts, how to repair a torn parchment with patient, respectful hands, and how to mobilize a community to protect its shared past from encroaching dunes and the eroding effects of humidity and neglect.

Hands-on preservation in a harsh climate

The work is labor-intensive and exacting. Manuscripts are often handwritten in Arabic, with occasional notes in local dialects. Conservation requires careful handling, climate-aware storage, and ongoing documentation of what exists today to ensure it can be studied tomorrow. In the desert climate, responding to temperature swings, dust storms, and insect threats becomes a routine part of life for those who care for the city’s knowledge base. Saif Islam embodies a practical, boots-on-the-ground approach: repairing bindings, reinforcing shelves, and organizing reading rooms so that studies can continue without interruption.

Community and global significance

Chinguetti’s libraries are more than archives; they are cultural crossroads. Scholars from neighboring regions and far-flung corners of the Islamic world have long visited to study manuscripts that illuminate centuries of trade, science, and philosophy. In recent years, international actors have begun to take notice of Mauritania’s heritage-at-risk, recognizing that protecting these libraries also protects a layer of human history that connects Africa, the Arab world, and beyond. Saif Islam’s work resonates beyond local borders because it speaks to a global duty: to preserve human knowledge against forces of erasure—whether they be deserts, political neglect, or climate change.

A future rooted in memory

Preservation demands more than repairs; it requires an ongoing vow to invest in education, infrastructure, and community involvement. Initiatives to train young conservators, digitize fragile texts where feasible, and coordinate with universities help ensure that the city’s “libraries” remain accessible to future generations. For Saif Islam, the mission is personal and communal: a promise that the whispers of the past will continue to guide the people of Chinguetti toward a more informed and connected future.

Conclusion: The desert as a teacher

The story of Saif Islam is a reminder that culture is not static. It is something people must protect, nurture, and pass on. In the courtyard of a timeless library, the 67-year-old guardian continues his work—one repaired binding, one cataloged manuscript, one saved page at a time—so that Mauritania’s city of libraries can endure as a beacon of learning in a shifting desert landscape.