Introduction: A World Watching, Yet a Lesson in Perspective

As nations set their sights on crewed lunar missions, the impulse to compare the moon program to terrestrial sovereignty disputes is understandable. The Moon, unlike the South China Sea, is not a patchwork of claims and counterclaims with conflicting maritime rights. Yet the temptation to frame this era as a modern space race—where national prestige, resource aspirations, and strategic influence collide—persists. The real opportunity, however, lies in reframing the conversation: recognizing how international cooperation, legal norms, and shared scientific goals can move the Moon beyond traditional sovereignty battles.

Rethinking the “Race”: What’s at Stake on the Moon

The immediate aims of lunar programs vary: testing life-support, practicing sustainable surface operations, and establishing a foothold for science and exploration. These are not purely national vanity projects. They hinge on complex scientific questions, infrastructure development, and the safety of crewed missions. By separating the rhetoric of a race from the practicalities of mission design, we can better assess what is feasible, what risks exist, and how collaboration can reduce costs and accelerate progress.

Legal Foundations: The Moon as a Global Commons

International law offers a distinct lens for lunar activity. The Outer Space Treaty frames celestial bodies as operations for the benefit of all humanity and prohibits claims of sovereignty over the Moon. The subsequent Artemis Accords and other cooperative frameworks have attempted to balance national interests with norms of transparency, interoperable standards, and peaceful exploration. While critics worry about loopholes or unequal access, the overarching message remains: space is not a theater for exclusive territorial conquest but a shared commons requiring inclusive governance.

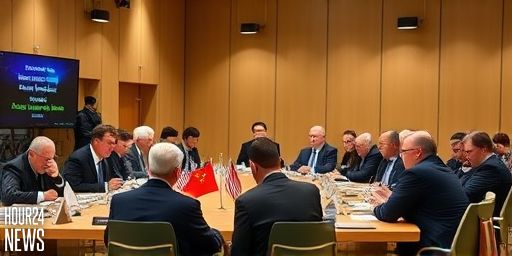

From Competition to Collaboration: Practical Pathways

There are concrete ways to reduce friction and increase cooperation as nations prepare for crewed lunar missions:

- Shared standards and interoperability: Establish common technical and safety standards for lunar landers, habitats, and communications to minimize duplication and risk.

- Data sharing and science diplomacy: Create open data policies for lunar orbiters, surface missions, and seismic/geophysical instruments to maximize scientific returns for all nations.

- Joint mission planning: Build international mission architectures that allow multiple countries to contribute modules, robotics, or science payloads in a coordinated framework.

- Legal and ethical guardrails: Strengthen norms around contamination, resource utilization, and dispute resolution to prevent frictions from escalating into confrontations.

Resource Claims: What Can Be Divided and What Should Be Shared

The Moon hosts resources that excite both policymakers and industry, from water ice to potential regolith-derived materials. Yet ownership and access are not straightforward. Rather than equating lunar resource exploitation with territorial claims, policy can emphasize licensed exploitation within a transparent, multilateral system. This approach preserves incentives for private investment while maintaining safeguards against competitive overreach that could jeopardize crew safety or international trust.

A Cultural and Moral Dimension: The Human Horizon

Beyond law and logistics, the Moon represents a mirror for humanity’s collective future. Cooperation on the Moon has the potential to strengthen norms of peaceful exploration, inspire innovation at home, and create shared benefits that extend to education, environmental monitoring, and technology transfer. Reframing the mission as a transnational endeavor helps depoliticize it, inviting diverse voices into the conversation about how space activities should be governed for the long term.

Conclusion: Charting a Stable, Inclusive Path Forward

The comparison to the South China Sea can be a cautionary tale about how disputes can derail shared ambition. But the lunar frontier also offers a chance to redefine competition as constructive collaboration. By grounding policy in international law, practical interoperability, and a genuine commitment to shared human progress, the next phase of crewed space exploration can become less a race for dominance and more a coordinated voyage for discovery.