Groundbreaking discovery ties Edinburgh to the Black Death

A team of researchers has uncovered the first scientific evidence of the Black Death in Edinburgh, based on the remains of a teenage boy who died in the 14th century. The discovery offers a rare glimpse into how the plague affected Scotland’s capital, supporting centuries of historical speculation with concrete biological data.

What was found and why it matters

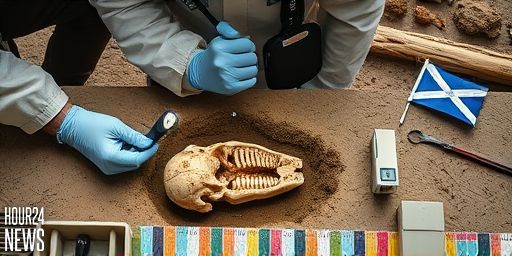

Scientists analyzed the skeletal remains and found a distinctive plaque on the child’s teeth containing indicators of Yersinia pestis, the bacterium responsible for the Black Death. The dental plaque, preserved over hundreds of years, provides a direct biochemical fingerprint that confirms the presence of the plague in Edinburgh during the mid-1300s. This kind of evidence moves beyond written records and archaeology alone, presenting a biological record of the outbreak’s reach in the city.

The significance for Edinburgh’s medieval history

Edinburgh’s role during the Black Death has been debated by historians for generations. The new findings place the city on a proven plague trajectory alongside other European urban centers that suffered staggering losses in the 1340s and 1350s. By pinpointing a local case, researchers can better map how the disease spread through trade routes, port towns, and crowded urban spaces of medieval Scotland. The teenage victim’s age also prompts questions about who was most vulnerable and how communities coped in the wake of such outbreaks.

How researchers conducted the study

The team employed microscopic and chemical analyses, including high-resolution imaging and molecular screening, to examine dental calculus—the mineralized plaque on teeth. By detecting pathogen DNA and specific biomarkers, they could confirm plague-era infection in a plausible timeframe. The multidisciplinary approach, combining archaeology, anthropology, and microbiology, underscores how modern science can illuminate past pandemics with unprecedented clarity.

Why this matters for understanding the Black Death

Historical narratives often describe the Black Death in sweeping terms. This discovery adds nuance by anchoring the event to a concrete individual in Edinburgh. It also helps researchers compare how quickly and intensely the plague spread through Scottish cities relative to England and continental Europe. Such comparisons can inform models of medieval disease transmission and the social consequences that followed the initial waves of mortality.

What’s next for the Edinburgh site

Ongoing excavations and analysis aim to build a broader picture of how the plague affected the local population. Future findings may reveal patterns of burial, community responses, and the long-term demographic impact on Edinburgh’s medieval residents. As more remains are studied, scholars hope to reconstruct a more comprehensive timeline of the 14th-century outbreak in Scotland’s capital.

Implications for modern understanding of pandemics

While the Black Death belongs to a distant era, the principle of examining biological traces in the archaeological record has contemporary relevance. The Edinburgh discovery demonstrates how pathogens leave lasting markers in human remains, offering lessons about disease dynamics, resilience, and the importance of public health measures during crises—lessons that resonate in today’s world as communities respond to emerging infectious diseases.

Conclusion

The identification of plague markers on a teenage boy’s teeth in Edinburgh marks a milestone in the study of medieval Scotland. It confirms a direct link between the city and one of the most devastating pandemics in human history and opens new avenues for understanding how the Black Death reshaped communities across the medieval north.