First Scientific Evidence of the Black Death in Edinburgh

A remarkable discovery by archaeologists provides the first scientific evidence that the Black Death reached Edinburgh in the 14th century. Remains from a teenage boy, discovered in a historic burial site, have yielded a startling clue: plaque on the child’s teeth contains DNA markers and pathogens associated with the bacterium Yersinia pestis, the agent behind the Bubonic plague. This finding places Edinburgh squarely within the line of cities affected by one of history’s most devastating pandemics.

The Find: Teeth, Plaque, and Pathogens

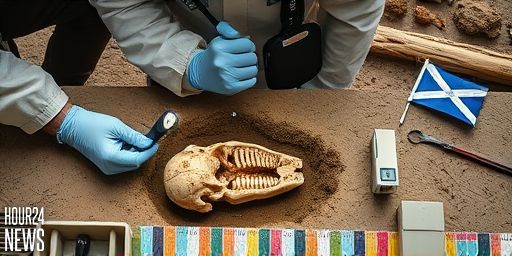

In examining the skeleton, researchers focused on dental calculus—hardened plaque that can trap microscopic material over a lifetime. Modern scientific techniques, including DNA sequencing and microscopic analysis, revealed genetic traces of Yersinia pestis in the teeth of the adolescent remains. This is one of the clearest cases to date of plague-related pathogens identified from a single individual in medieval Scotland, offering direct evidence that the disease circulated in the capital city during the 14th century.

What This Means for Edinburgh’s History

The Edinburgh discovery complements growing evidence of the Black Death’s reach across the British Isles. While historical records describe outbreaks in the 1340s and later, having material proof from Edinburgh helps historians map the disease’s spread through urban centers and its impact on medieval society. The find reinforces epidemiologists’ understanding that plague moved along trade routes and urban networks, shaping population decline, labor dynamics, and social upheaval in Scotland at the time.

How Scientists Confirm the Presence of Plague

Scientists use a combination of techniques to confirm plague exposure in ancient remains. Dental calculus is particularly valuable because it preserves biological material long after soft tissues decay. In this case, researchers extracted DNA and looked for fragments characteristic of Yersinia pestis, along with contextual markers that distinguish ancient pathogens from modern contaminants. Additional analysis, such as radiocarbon dating and isotopic studies, helps place the individual in a precise timeframe, strengthening the link to the 14th-century pandemic.

Broader Context: The Black Death and Medieval Scotland

Scholars have long debated how quickly the Black Death reached Scotland and how it affected urban life. Edinburgh, with its status as a major trading hub, would have been vulnerable to incoming waves of infection carried by merchants and travelers. This discovery adds a tangible dimension to those debates, illustrating that the disease touched individuals at the heart of Scotland’s capital far earlier than some written accounts indicate. It also highlights the importance of dental anthropology and ancient DNA studies in reconstructing pandemics that left few written traces.

Looking Ahead: What Comes Next

As researchers reexamine other medieval burials in Edinburgh and across Scotland, more cases of plague-related pathogens may emerge from dental calculus and skeletal remains. Each new finding helps refine timelines, transmission models, and the social ramifications of the Black Death. The Edinburgh teenager’s teeth thus become a crucial data point in a larger story about how a global catastrophe reshaped local communities millennia ago.