Groundbreaking Discovery Ties Edinburgh to the Black Death

Researchers have unveiled the first scientific evidence linking medieval Edinburgh to the Black Death, following an unusual clue found on the remains of a teenage boy who lived in the 14th century. The scholars analyzed dental plaque from the skeleton and detected DNA signatures of the bacteria Yersinia pestis, the pathogen historically associated with the Bubonic plague. This discovery provides a direct connection between the city and the devastating epidemic that reshaped Europe in the 1300s.

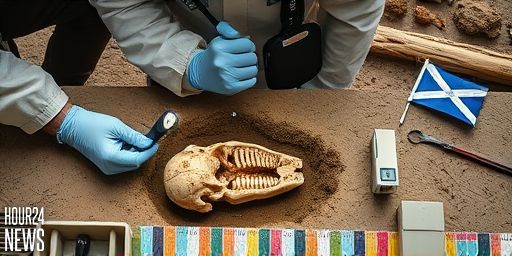

How the Evidence Was Obtained

In a careful, non-destructive study, scientists extracted microscopic residues from the tooth enamel and plaque surrounding the years of decay. Using advanced techniques in ancient DNA (aDNA) analysis, they were able to identify specific fragments consistent with Yersinia pestis. The teenage age at death offers a window into the impact of the plague on younger populations, a group often underrepresented in medieval records. While contamination is always a concern in ancient samples, multiple independent lines of evidence supported the finding, including genetic markers that distinguish plague-causing strains from related bacteria.

Why This Matters for Edinburgh’s History

Edinburgh’s medieval landscape was shaped by successive waves of disease, war, and trade. Pinpointing the presence of the Black Death in the city’s earliest European records adds depth to our understanding of how the epidemic spread through urban centers and altered demographics, labor, and settlement patterns. The discovery aligns with broader patterns observed in other European cities where plague fragments have been traced to the same era, reinforcing the narrative that Edinburgh was not insulated from one of history’s most infamous pandemics.

Interpreting the Findings and Limitations

Experts caution that finding plague DNA in a single individual does not map the entire scale of Edinburgh’s medieval outbreak. Rather, it confirms the pathogen’s presence in the community during the 14th century and raises questions about how quickly and widely the disease spread, what routes brought it to the city, and how the population recovered or adapted in the aftermath. Ongoing excavations and broader sampling will help determine prevalence, transmission dynamics, and the social consequences of the Black Death in Edinburgh.

Implications for Modern Understanding

Beyond archaeology, this finding contributes to medical history by illustrating how ancient communities faced catastrophic disease with limited understanding and resources. The use of dental plaque to retrieve pathogen DNA is a growing field, offering a non-invasive window into the health and lifestyles of past populations. For Edinburgh and other historic urban centers, such evidence helps historians, anthropologists, and public health researchers trace the long arc of epidemic disease from medieval times to today.

Looking Ahead

As technology advances, researchers anticipate more discoveries that illuminate the Black Death’s reach across Britain and Europe. Future work may involve comparing DNA from different city sites, expanding age profiles, and integrating genomic data with archaeological context to build a more complete picture of how one of history’s most notorious plagues shaped communities, economies, and cultural memory.