Introduction: The Curious Question of Wet Planets

From our own world to distant exoplanets, the presence of liquid water is a defining factor for habitability. But how do planets acquire their water in the first place? Recent research published in Nature by Carnegie scientists suggests a compelling mechanism: water can be generated during the planet’s formative years, through interactions between molten surfaces and early atmospheres.

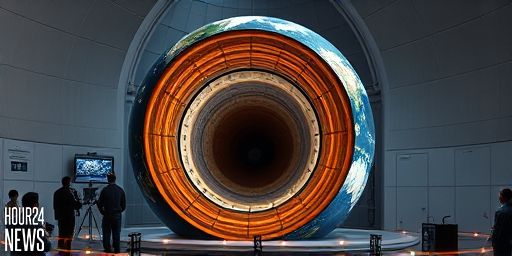

Magna Ocean Chemistry: A Crucible for Water Formation

In the hot, early stages of planetary development, a planet often hosts a magma ocean—a global layer of partially molten rock. As this magma cools and differentiates, it exchanges gases with the evolving atmosphere. The experiments and modeling from the study indicate that water can be produced through high-temperature reactions in the magma, releasing hydrogen and oxygen carriers that combine to form water in the nascent atmosphere and ocean reservoirs.

Primitive Atmospheres: The First Water Reservoirs

Early planets do not have water oceans at birth. Instead, they possess thick, primitive atmospheres composed of gases captured from the protoplanetary disk. These atmospheres interact with the underlying magma, acting as sinks and sources for hydrogen, oxygen, and hydroxyl groups. As the planet cools, these chemical exchanges favor the buildup of liquid water, potentially creating substantial surface oceans even before late-stage delivery from comets or asteroids.

Why This Matters for Water-Rich Worlds

If water can form during planet formation, it broadens the range of worlds that might harbor oceans. Planets that form in diverse environments—around different stars and at various distances from their suns—could still accumulate significant water inventories without relying solely on external delivery. This mechanism helps explain why some rocky planets may become water-rich early in their histories, setting the stage for long-term climate stability and potential habitability.

Connecting Theory with Observations

The Nature study combines laboratory experiments with theoretical modeling to show that water generation is a plausible outcome of magma-atmosphere chemistry. While direct observation of these early-stage processes is challenging, the researchers point to signatures in rocky planets’ atmospheres and interior compositions that future missions could verify. In the coming years, telescopes and space probes may detect indications of primordial water pathways in young planetary systems, reinforcing the idea that water is embedded in planetary birthright rather than solely acquired later.

Implications for the Search for Life

Water is a key ingredient for life as we know it. If planets can form water reservoirs before other late-stage processes, this increases the number of worlds where life could eventually emerge. It also refines targets for future exploration, suggesting that some planets previously deemed marginally habitable might house surprising oceans formed in their earliest epochs.

Next Steps for Researchers

Researchers aim to refine the physical and chemical models of magma ocean–atmosphere interactions, explore how different planetary masses and compositions affect water production, and identify observable markers that spacecraft can seek in young planetary systems. By triangulating experimental data with telescopic observations, scientists hope to map how common water-rich planets are across our galaxy.