A discovery in Western Australia reshapes Earth’s early history

Planet Earth’s early years were a brutal place. The surface was frequently scarred by space rocks as the young planet cooled, atmosphere formed, and life began its slow climb. The latest fieldwork from Curtin University raises the stakes in this story: a site in Western Australia’s Pilbara region could host the oldest meteorite impact crater yet discovered on Earth. If confirmed, the find pushes back the clock on planetary bombardment and offers fresh insight into the conditions that shaped our planet’s early environment.

Where and what was found

The rocks studied lie at North Pole Dome, about 40 kilometres west of Marble Bar in the Pilbara. The area is renowned for preserving some of Earth’s earliest crust, making it a natural laboratory for unraveling the planet’s ancient past. In these rocks, researchers identified shock textures and microscopic patterns consistent with intense heat and pressure—signatures that only a colossal meteor impact could produce.

Shatter cones, distinctive rock formations formed under extreme impact forces, provided a telling clue. Measuring these features and dating the surrounding rock allowed the team to estimate an age for the event at about 3.5 billion years. If verified, this crater would be far older than the famous Chicxulub impact that roughly marks the end of the dinosaurs and signals a dramatic, planetary-scale event about 66 million years ago.

What the 3.5-billion-year date could mean

“Before our discovery, the oldest confirmed impact crater was around 2.2 billion years old,” said a member of the Curtin team. “This new site suggests Earth experienced massive extraterrestrial impacts hundreds of millions of years earlier than previously thought.” The implications are broad. A crater of this magnitude could have influenced the atmosphere, altered early climate conditions, and affected the trajectory of early life’s emergence. In brief, it adds a new layer to the story of Earth’s formation and its evolving geology.

Two sides of the debate

Science advances through questions, replication, and debate. In July 2025, Harvard researchers published a different interpretation. Their fieldwork proposed a younger event—around 2.7 billion years ago—producing a crater about 16 kilometres wide in a separate region of Western Australia. This contradicts the Curtin date and highlights the challenges in precisely dating ancient impact events, where burial, metamorphism, and later geological processes can obscure the original signals.

Why disagreement is part of science

Rather than a polarizing clash, the two findings illustrate how science works. Competing hypotheses invite more data, more samples, and more refined dating techniques. The scientific method thrives on verification, not victory. Each new study adds detail to the evolving map of Earth’s early bombardment history and helps scientists understand how such impacts might have shaped the planet’s atmosphere, crust, and plate tectonics long before complex life appeared.

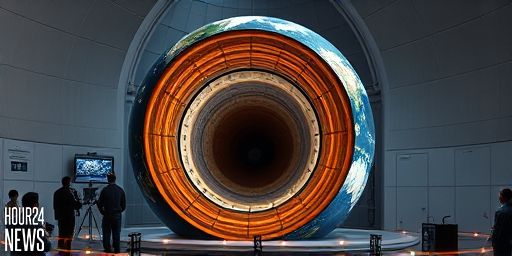

The bigger picture: Earth’s ancient bombardment and life

Whether the oldest confirmed crater sits at 3.5 billion or around 2.7 billion years, the underlying narrative remains: Earth has long been a stage for violent cosmic events that influenced its atmosphere, geologic regime, and perhaps even the origin of life. The Pilbara discovery emphasizes how much remains to be learned about the early, volcanic, and collision-rich chapters of our planet’s history. Each piece of evidence brings us closer to a coherent account of how Earth evolved from a tumultuous early world to the planet we inhabit today.

What’s next for researchers

In science, certainty comes with replication and new data. The WA site will continue to be studied with more precise dating, deeper sampling, and cross-comparison with other ancient crustal regions around the world. The dialogue between Curtin and Harvard researchers—and any future teams—will likely refine the age estimate and the crater’s original size. Whatever the outcome, Western Australia’s geology is already rewriting a chapter of Earth’s early history.