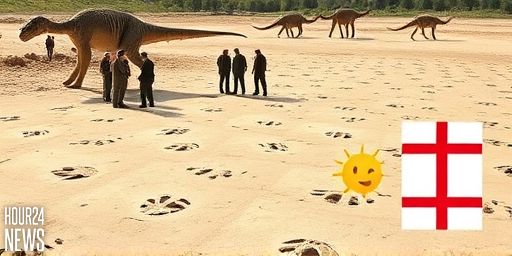

Groundbreaking Discovery at Dewars Farm Quarry

In 2024, a major paleontological discovery unfolded at Dewars Farm Quarry near Bicester in Oxfordshire, England. A collaborative team from the University of Oxford, the University of Birmingham, Liverpool John Moores University, and the Oxford University Museum of Natural History unearthed around 200 additional footprints, forming four distinct trackways. Among these, one trackway stands out as Europe’s longest sauropod dinosaur trackway, marking a milestone in the study of long-necked herbivores from the Middle Jurassic period.

What the Tracks Tell Us About the Middle Jurassic

The newly exposed footprints date back roughly 166 million years, to a time when Europe’s coastline and inland environments looked very different from today. The tracks belong to sauropods, a group of large-bodied, long-necked herbivores that included iconic dinosaurs like Cetiosaurus. The trackways provide a rare, direct glimpse of how these giants traversed ancient landscapes and interacted with their surroundings.

The Record-Breaking Trackway

Spanning approximately 220 meters from the first to the last exposed footprint, Europe’s longest sauropod trackway at Dewars Farm Quarry stretches across a broad north-south axis. The length and preservation of these prints offer researchers a unique chance to study gait, stride length, and the potential size of the dinosaurs responsible for the tracks. The long trackway is complemented by three additional, shorter trackways discovered in the same surface area. One of these shorter sequences resurfaces a continuation of prints first found in 2022, hinting at an extensive, connected parking of prints that could, with further exposure, reveal an even longer overall trackway.

A Diverse Field of Fossil Clues

Beyond the prominent sauropod footprints, the site yielded marine invertebrates, plant material, and a crocodile jaw. These accompanying finds enrich the paleontologists’ understanding of the ecosystem that supported these dinosaurs and how their tracks ended up preserved in the sediments. Each new piece adds to a layered narrative about climate, flora, and the sedimentary processes that captured these momentary acts of massive animal movement millions of years ago.

Why Footprints Matter in Dinosaur Research

Footprints reveal aspects of dinosaur life that skeletal remains alone cannot. They illuminate locomotion, behavior, social dynamics, and even interaction with other species. As University of Birmingham Professor Richard Butler notes, “Most of what we know about dinosaurs comes from their skeletons, but footprints and the sediments that they are in can provide valuable additional information about how these organisms lived and what their environment looked like over 166 million years ago.”

The Ongoing Excavation and Future Prospects

The field team spent seven days methodically studying a surface that had become noticeably drier and harder, focusing on around 80 exceptionally large footprints up to 1 meter long. These prints form a cohesive, long-running trackway that captivates both scientists and the public with its scale. The researchers plan systematic sediment sampling as part of ongoing work to decode the environment that created and preserved the trackways. Initial findings from these analyses are already shaping hypotheses about sedimentary conditions, water presence, and how such tracks recorded ancient weather patterns.

Looking Ahead for Dewars Farm

As more of the footprint surface is likely to be revealed in the coming years, paleontologists anticipate a fuller, richer description of the site’s significance. The consortium foresees that future work will not only refine measurements of the trackways but also illuminate the broader context of Middle Jurassic ecosystems in Europe, potentially redefining how we map and interpret dinosaur movements across vast landscapes.