New Findings Reframe Mimas as an Ocean World Candidate

Saturn’s small, cratered moon Mimas has long been dismissed as a frozen relic, best known for its prominent Herschel Crater. Yet a growing body of research is challenging that view. Recent thermal and orbital models indicate that a young subsurface ocean could lie beneath 12–19 miles (20–30 kilometers) of ice. If confirmed, Mimas would join a small group of worlds in the solar system where liquid water might exist beneath an icy shell, prompting a rethink of how scientists define ocean worlds.

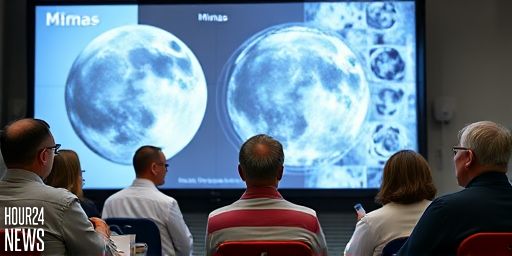

“When we look at Mimas, we don’t see any of the things that we’re accustomed to seeing in an ocean world,” said Alyssa Rhoden, a planetary scientist at the Southwest Research Institute in Colorado. Speaking at the Europlanet Science Congress–Division for Planetary Sciences meeting, she summarized the core idea: hidden liquid water could be sculpting the moon’s interior long after surface processes have frozen over. The notion comes from a combination of thermal history, orbital dynamics, and the way tides can generate heat inside an icy shell.

How Subsurface Oceans Could Form on Ice Worlds

The Cassini spacecraft first hinted that Mimas might host more internal warmth than expected, but the latest work builds a stronger case. The researchers focused on how gravitational interactions with Saturn and the Moon’s own rotation could produce tidal flexing. This flexing converts orbital energy into internal heat, potentially melting portions of the icy crust and creating liquid pockets beneath the surface. The result, in a geological blink of an eye, could be a layered interior with a relatively young ocean separating a hard shell from a rocky core.

Rhoden’s team points to changes in Mimas’ orbit over the past 10 to 15 million years as a key driver. “Tidal heating would have melted parts of the ice shell in this timeframe,” she explained. While the surface remains pocked with craters, the interior could tell a different story, one in which liquid water persists in pockets or layers beneath the ice layer. Detecting such an ocean would be challenging yet not outside the realm of possibility for a future mission.

What the Implications Could Be for Ocean World Classifications

The prospect of a young subsurface ocean on Mimas has implications beyond one small moon. Scientists use multiple criteria to classify ocean worlds, including the presence of liquid water, energy sources to sustain it, and the potential for chemical disequilibria that could support life. A confirmed ocean on Mimas would expand the catalog of candidate worlds where life could, at least theoretically, arise or be sustained, even if conditions are extreme by Earth standards.

Alyssa Rhoden’s colleague Adeene Denton has been investigating Herschel Crater, Mimas’ most striking surface feature. Her work suggests the crater formed at a moment when the ice shell was still soft but not fully liquid, implying a dynamic interior in which melting and refreezing cycles might have occurred. Denton described the findings as helping to “tighten” the historical narrative of Mimas, moving from a rigid, uniformly frozen body to a moon with a complex, evolving interior.

What Comes Next for Mimas Exploration

Even as the current models are compelling, scientists are careful not to overstate certainty. Direct evidence of liquid water beneath Mimas’ crust would require a mission capable of probing the interior, possibly through gravity measurements, magnetic field studies, or radar sounding that can peer through thick ice. Rhoden noted that such a mission would be difficult but potentially feasible in the long term, underscoring the value of continued modeling and mission planning in solar system exploration.

“There would be challenges, but it may be doable,” Rhoden said, leaving open the door to future investigations that could confirm or refute the presence of an ocean beneath Mimas’ icy shell. For now, the convergence of thermal, orbital, and crater history data paints a coherent, if tentative, picture of a moon that defies its reputation as a frozen relic.

As researchers build a more complete narrative around Mimas, the moon is increasingly viewed not as a dead rock but as a dynamic world with a hidden lake. If future observations corroborate these findings, Mimas could become a touchstone in understanding how oceans might exist in unexpected places across the solar system, reshaping goals for future explorations of small, icy worlds.