The Unexpected Toolmakers: Paranthropus and Oldowan Technology

For decades, the story of our cognitive and technological origins centered on the genus Homo. The prevailing view was that tool-making began with Homo habilis and spread through later species. A groundbreaking study published in Science challenges this narrative, presenting compelling evidence that Paranthropus, a robust, early hominin lineage that thrived in Africa for about 1.5 million years, may have used—and perhaps even crafted—stone tools. If confirmed, these findings push the roots of Oldowan technology further back in time and redefine what we consider the first technological revolution in human evolution.

Rethinking Oldowan Technology and Its Makers

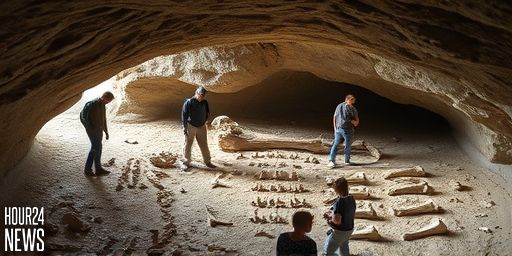

Oldowan technology, characterized by simple flakes and cores, has long been cited as the earliest form of stone tool technology. The new discoveries reveal stone tool assemblages found in close association with Paranthropus fossils, suggesting that the capability to manipulate stone may not have been exclusive to Homo. As lead author Professor Thomas Plummer notes, these may represent “one of the oldest—if not the oldest—examples of Oldowan technology anywhere in the world.”

What makes this claim especially provocative is not just the presence of tools but their context. The tools appear integrated into the ecosystem of Paranthropus sites, implying intentional use and possibly even early manufacture. This challenges the assumption that Paranthropus, often characterized by a heavy build and a relatively modest brain, was limited to specialized plant processing. The door is opened to the possibility that early hominins shared more sophisticated behaviors than previously credited to non-Homo lineages.

Diet, Behavior, and Survival in a Dynamic Environment

The implications of tool use for Paranthropus extend well beyond the mere existence of artifacts. The associated findings hint at a dynamic and adaptable diet, one capable of incorporating a broader range of food sources. Professor Fred Spoor argues that the toolkit “was more widely distributed at an earlier date than people realized,” enabling Paranthropus to process both plant and animal tissues. The tools may have allowed access to resources that would have been out of reach with teeth alone, signaling a flexible strategy in a challenging African savannah.

Dr. Rick Potts, a senior author, captures the transformative potential of these abilities: “With these tools, ancient hominins can crush better than an elephant’s molar and cut better than a lion’s canine.” The statement underscores how tool use could amplify dietary breadth, facilitating the exploitation of tough plant materials and animal tissues alike. Such versatility would have been a decisive survival advantage during environmental fluctuations and resource scarcities.

Timeline Tensions: When Did Tool Use Begin?

The new evidence reshapes the timeline of technological innovation. If Paranthropus indeed contributed to Oldowan technology, then the emergence of tool use predates the first Homo fossils by several hundred thousand years. This reframes our understanding of cognitive and cultural evolution, suggesting that the roots of technology were planted earlier in the hominin lineage than once thought. As Spoor emphasizes, this pushes back the date when early hominins began to manipulate their environments beyond instinctive behavior, opening new questions about learning, social transmission, and communal problem-solving in the deepest chapters of human ancestry.

Broader Implications for Human Evolution

These discoveries extend beyond Paranthropus. If a robust, small-brained lineage could harness tools to adapt to shifting ecological landscapes, other early hominins may have shared in this ingenuity before Homo emerged as the dominant lineage. The findings encourage a reevaluation of early hominin capabilities, highlighting the possibility that technological prowess was not a unique hallmark of Homo but a trait distributed across multiple branches of our family tree.

Conclusion

As researchers continue to analyze site contexts, mineral compositions, and use-wear patterns on these tools, the narrative of our technological origins remains compellingly unsettled. The idea that Paranthropus could have invented or at least widely used stone tools invites a broader view of early human evolution—one where innovation, diet, and survival strategies emerged through shared ancestry and adaptive ingenuity long before Homo dominated the scene.