The Longest-Lived Spider: Number 16’s Record-Setting Life

In the annals of arachnology, Number 16 stands out as a rare beacon of longevity. A Gaius villosus spider living in Western Australia, she defied typical spider lifespans by surviving for an astonishing 43 years. This remarkable life wasn’t just a personal milestone; it became a window into how trapdoor spiders endure, reproduce, and interact with their ecosystem over decades.

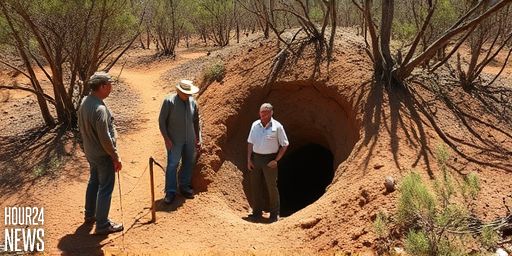

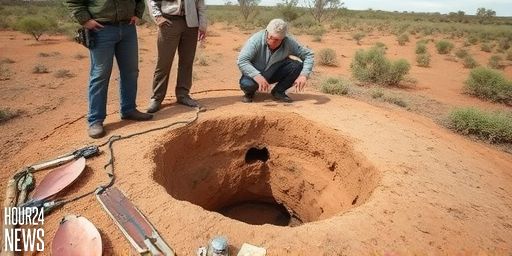

The story of Number 16 is tightly linked to a long-term field study initiated in 1974 by the pioneering arachnologist Barbara York Main at the North Bungulla Reserve near Tammin, in South-Western Australia. The project focused on population dynamics and behavior of trapdoor spiders, a group known for their sedentary lifestyle and complex burrow-based existence. Over the years, researchers tracked dozens of individuals, but Number 16’s longevity became the centerpiece of the work and a touchstone for understanding the species’ life-history traits.

Why Number 16 Lived So Long

Researchers found that Number 16’s extraordinary lifespan was not a random accident but the product of several biological and ecological factors. The trapdoor spider’s life cycle includes living in undisturbed native bushland, a highly sedentary existence, and a remarkably low metabolism. These traits minimize energy expenditure and reduce exposure to predators and environmental stressors, allowing individuals to persist in a relatively stable niche for decades.

As Leanda Mason, a biologist involved in the study, explained, the combination of a secluded burrow life, low metabolic rate, and stable habitat contributed to the spider’s impressive tenure. Rather than roaming far and wide in search of food, Number 16 relied on patience and camouflage, occupying the same burrow and ecosystem for most of her life. This energy-efficient strategy is a hallmark of mygalomorph spiders and helps explain how they can survive in resource-limited environments.

Life in the Burrow: A Strategy for Sustainability

The long-term study revealed that Number 16 sustained herself by waiting for prey to venture near the burrow’s entrance. This predator strategy reduces energy costs while ensuring a steady, if modest, intake of nourishment. In a world where many spiders are highly mobile, Number 16’s sedentary lifestyle offered an ecological advantage—one that translated into decades of survival in a challenging desert-maritime climate of Western Australia.

The Tragic, Yet Informative Ending

Number 16’s life came to an unexpected end in 2016 due to a parasitic wasp that pierced the burrow’s lid and invaded her body. Parasitic wasps lay eggs inside their hosts, and the developing larvae ultimately kill the host from within. Notably, researchers had observed her alive just six months prior, underscoring the fragility that can accompany even the most venerable survivors. In their report, scientists stated, “Having been seen alive in the burrow six months earlier, we therefore report the death of an ancient G. villosus mygalomorph spider matriarch at the age of 43.”

Her passing was a poignant reminder that natural systems are balanced by both remarkable resilience and inherent vulnerability. The discovery offers a cautionary tale about parasitism and predator-prey dynamics in the wild, and it enriches our understanding of the daily risks faced by long-lived species.

Lessons for Conservation and Humans

Number 16’s life embodies sustainability in nature. A low-impact, burrow-bound existence illustrates how some species thrive with minimal resource use. This model of efficient energy use and habitat stability echoes human conservation goals: protect undisturbed habitats, reduce unnecessary disturbances, and recognize the importance of long-term ecological monitoring. The spider’s story reinforces the value of patient, methodical research to uncover the intricate life histories that shape biodiversity.

Ultimately, Number 16’s 43-year journey—from a modest field note to a celebrated case study—remains a powerful testament to the wonders of natural history and the ongoing need to safeguard fragile ecosystems in Western Australia and beyond.