Rare Find on the Jurassic Coast: A New Ichthyosaur Emerges

Scientists have announced the discovery of a near-complete ichthyosaur skeleton that belongs to a brand-new species, Xiphodracon goldencapensis, nicknamed the “Sword Dragon of Dorset.” Unearthed near Golden Cap along the UK’s famous Jurassic Coast, this dolphin-sized marine reptile lived roughly 190 million years ago during the Early Jurassic, a critical interval in ichthyosaur evolution.

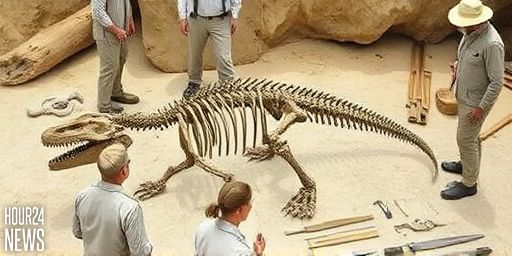

The skeleton’s preservation is exceptional, offering a three-dimensional view of the animal and revealing features never before seen in ichthyosaurs. The skull is notable for its enormous eye socket, and the snout resembles a long, sword-like blade—hence the species’ evocative name. Researchers estimate the animal reached about three meters in length and preyed on fish and squid in the ancient seas.

Discovered in 2001 by Dorset fossil collector Chris Moore, the specimen was eventually acquired by the Royal Ontario Museum in Canada. For years, the fossil sat largely unstudied in storage, making its re-emergence and formal description all the more remarkable. When the international team led by Dr. Dean Lomax revisited the find, they recognized it as a previously unknown lineage that fills a gap in the ichthyosaur record from the Pliensbachian stage (roughly 193–184 million years ago).

This period is one of the most intriguing chapters in ichthyosaur evolution, marked by a faunal turnover in which some families vanished and others appeared. Xiphodracon goldencapensis provides a crucial data point for pinpointing when those shifts occurred and how quickly new lineages diversified in the wake of mass changes in the marine ecosystem.

What Makes Xiphodracon Unique?

Among its most striking traits is a lacrimal bone with prong-like projections around the nostril, a configuration not observed in other ichthyosaurs. The limb bones and teeth show signs of deformation, suggesting injury or disease during life, while the skull bears evidence that a larger predator may have attacked the animal. These details offer a rare glimpse into the daily dangers of Mesozoic oceans and the ecological dynamics at play in the Jurassic seas surrounding Britain.

Lead author Dr. Dean Lomax explains that the specimen’s completeness is what makes it so valuable. “One of the coolest things about identifying a new species is that you get to name it,” he notes. The name Xiphodracon—derived from Greek and Latin roots for sword and dragon—honors both the distinctive snout and the long-held idea of ichthyosaurs as sea dragons in popular culture for more than two centuries.

The discovery also helps clarify the geographic and temporal patterns of ichthyosaur diversity. Prof. Judy Massare of the State University of New York at Brockport emphasizes that while Pliensbachian ichthyosaurs are rare worldwide, Xiphodracon’s features—especially its early appearance in the Early Jurassic—suggest a more complex evolutionary story than previously understood. Dr. Erin Maxwell from the State Museum of Natural History Stuttgart adds that the skeleton sheds light on the ecology and lifestyle of Jurassic Britain’s marine communities, beyond just anatomy.

A Window into the Past

With its near-perfect preservation in three dimensions, Xiphodracon goldencapensis stands as a rare, almost fully intact record from the Pliensbachian. It gives scientists a tangible link to a time when life in the seas was dynamic and often perilous, and it helps fill longstanding gaps in the ichthyosaur fossil record. The skeleton will be displayed at the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto, Canada, allowing the public to glimpse a creature that lived hundreds of millions of years ago and to marvel at the intricate record it leaves behind.

This discovery underscores the enduring value of museum collections, fieldwork along the Jurassic Coast, and the collaborative effort of paleontologists across continents in decoding Earth’s deep history.