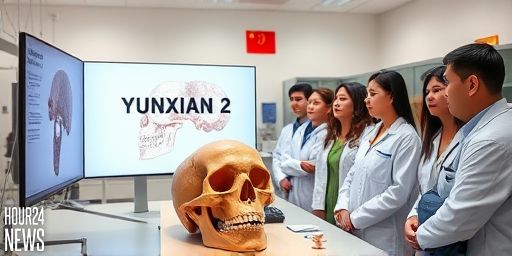

Reconstructing a fossil as a new scientific reference

The Yunxian 2 skull, unearthed in Hubei and dated to roughly 940,000–1.1 million years ago, has become a case study in how modern methods transform archaeology into a testable science. In a Nature publication by María Martinón-Torres, Wu Xiujie, José María Bermúdez de Castro, and colleagues, the skull’s damaged state is not treated as a final judgment but as a challenge that a precise pipeline can overcome. High-resolution computed tomography, structured light scanning, and virtual modeling are combined with systematic comparisons to more than a hundred hominin specimens. The aim is not to polish a fossil but to render its geometries transparent, reproducible, and open to scrutiny by the broader scientific community.

In this sense, Yunxian 2 becomes a reference object rather than a solitary relic. The authors stress methodological transparency: every deformation and every assumption involved in the reconstruction is documented so that other researchers can replicate the results or challenge them with alternative models. This epistemic clarity is what gives the finding intellectual traction beyond the immediate specimen and helps turn a damaged skull into a node of ongoing scientific debate.

What Yunxian 2 reveals about Eurasian lineages

The morphological readout from the restored skull places it closer to the clade associated with Homo longi and, more broadly, to Denisovan-related lineages than to classic Homo erectus. The combination of a long, relatively low cranium and an unusually roomy endocranial volume for its age, complemented by distinctive facial traits, suggests a deep Asian ancestry for a lineage that diverged from the main Homo lines earlier than many standard timelines would allow. If Yunxian 2 indeed belongs to this deep Asian lineage, the divergence among the major human groups—modern humans (sapiens), Neanderthals, and Denisovans—may have occurred earlier than previously thought, possibly by more than a million years.

These results contribute to a nuanced view of human evolution in Asia. They challenge a simplistic narrative of a late, single exit from Africa and invite us to consider that Asia harbored varied human lineages with complex interactions. The skull does not erase Africa’s central role in our species’ emergence, but it does relocate Asia from a peripheral stage to a central, interactive actor in evolutionary history.

From Out of Africa to a connected, multicentral story

Proponents of the traditional African replacement model will not be easily persuaded to abandon Africa as the cradle of Homo sapiens, given the strength of genomic data. Likewise, strict multiregionalism, with parallel evolutions toward modern humans, is at odds with gene flow and shared ancestry signals. Yunxian 2 points to a middle path—an Africa-centered origin for the appearance of our species, coupled with deep, interacting lineages in Asia and Eurasia that diverged earlier than expected and later interfaced with sapiens. This yields a “connected multicentrality”: a reticulated evolutionary history in which multiple regions contribute threads to the same fabric of humanity.

In this view, the Out of Africa paradigm does not die, but it becomes more intricate. The single arrow of migration is replaced by networks of waves, exchanges, and back-and-forth movements. Thus, a reimagined fossil record must be read with care: a single skull can illuminate broad patterns but cannot substitute for a fuller sequence of fossils and, ideally, biomolecular data that may someday confirm deep divergences.

Philosophical implications: science in the era of uncertainty

The Yunxian 2 case offers rich fodder for philosophy of science. It shows how a well-restored fossil can calibrate taxonomic interpretations while remaining vulnerable to critique. The methodological auxiliaries—deformation models, symmetry criteria, reference samples—are acknowledged rather than concealed. Philosophers of science and scientists alike embrace this openness: predictions follow, but they must be tested, and the hypothesis remains provisional until the data accumulate further support or refutation.

Ethical and future considerations

If Asia preserves deep branches of humanity, the ethical stakes extend to how fossil heritage is stewarded and studied. A plural, collaborative research culture helps avoid epistemic colonialisms and enriches the conversation about origins with multiple perspectives and communities involved in the discourse.

Conclusion: a braid of human origins

Yunxian 2 invites us to see human history as a reticulated forest rather than a straight trunk. Should subsequent findings strengthen this view, our shared past becomes a braid of intertwined lineages, with Africa as the cradle and Asia as a vital, dynamic contributor. In that sense, a crushed skull teaches us not only about ancient faces but also about the openness and humility required to study who we are today.