In 1990, a long-studied skull kept in a museum drawer became the unlikely center of a scientific catapult. Dated to roughly one million years ago, it had for years been cited as a classic Homo erectus specimen—the archetype many researchers used to map the early spread of humanity. Then, a small team unveiled something unexpected: a virtual reconstruction of the skull revealed a cranial profile and dental traits that did not comfortably fit the Homo erectus template. The shift was subtle at first, tucked into a technical report, but the implications were anything but subtle. If this skull truly belongs to a different lineage, the very timeline we use to describe human evolution could be rewritten.

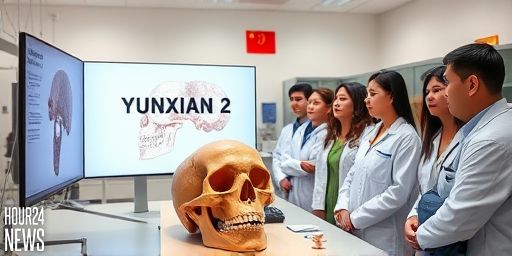

The discovery and its surprising reclassification

The team reexamined the fossil with modern tools that were not available when the skull was first analyzed. High-resolution imaging, digital endocasts, and biomechanical modeling allowed researchers to compare thousands of features with a precision previously impossible. While some traits echoed Homo erectus, others resembled earlier forms and still other features hinted at a lineage that would destabilize a neatly linear story of human origins. The work does not declare a new species with certainty, but it does raise the possibility that this million-year-old skull resides on a side branch of the human family tree, or perhaps at a juncture where multiple populations intermingled. These are exactly the kinds of complexities that paleontologists now associate with a more mosaic view of evolution rather than a single, tidy ladder.

The virtual reconstruction revolution

What makes this development noteworthy is not merely the draught of a single cranial shape but the method itself. Virtual reconstruction—born from advances in CT scanning, 3D modeling, and comparative anatomy—lets scientists create a lifelike digital replica of a fossil, test its biomechanics, and simulate growth patterns under various evolutionary scenarios. In this case, the researchers overlayed the skull with digital models of Homo erectus, Homo habilis, and archaic Homo sapiens-like forms to assess compatibility. The result is a more nuanced conversation about what features actually signify a species boundary versus what features arise from environmental pressures or individual variation. The technique, once a curiosity of a few laboratories, is becoming a driving force in paleontology and anthropology, expanding the evidence base beyond the physical fossil alone.

Implications for the timeline of human evolution

If confirmed, the misclassification would ripple through the historical framework used to place key milestones in human evolution. Questions would arise about when certain cranial adaptations emerged, how quickly populations dispersed, and how different hominin groups influenced one another. A skull that defies the Homo erectus label could imply that some traits we once associated with a later stage appeared earlier, or conversely, that they developed along different lines altogether. The broader narrative—one of branching lineages, regional variation, and occasional interbreeding—gains fresh urgency as researchers recheck other fossils that might fit or contest this reimagined geography of ancestry.

What this means for Homo erectus and related lineages

Paleontologists emphasize caution. A single specimen, even when backed by powerful new tools, does not rewrite the entire timeline. The finding invites a reexamination of other well-known skulls from the same period and a renewed search for additional fossils to fill gaps in the record. In the meantime, the field moves toward a more probabilistic, mosaic view of human origins, one that accommodates both shared traits across lineages and distinctive features that suggest divergent evolutionary paths, sometimes in different continents at roughly similar times.

Science in conversation: skepticism and verification

As with any major reinterpretation, skepticism is essential. Peers will scrutinize the methods, the reproducibility of the virtual model, and the criteria used to judge which features count as diagnostic for classification. Replication with new fossils, independent remeasurements, and cross-lab validation will determine whether the skull remains a provocative anomaly or becomes a catalyst for a real paradigm shift. The slow pace of scientific consensus often means that revolutionary ideas enter the discourse through cautious, incremental steps, rather than dramatic announcements.

Beyond the skull: a mosaic of humanity

Ultimately, this development nudges us toward a richer, less linear understanding of human evolution. The million-year skull challenges us to ask what makes us human: a single class of traits, or a dynamic ensemble shaped by time, place, and collaboration among multiple populations. In the laboratory, in the field, and in the years ahead, researchers will continue to test, refine, and debate these ideas, shaping a narrative that more accurately reflects the messy, interconnected history of our species.