The Thumb That Helped Rodents Conquer the World

Rodents, a colossal group with more than 2,500 species, occupy almost every corner of the globe. A recent synthesis of museum archives, field observations, and scientific literature suggests that a tiny feature on their paws may have played a disproportionate role in their success: a flat nail on the thumb. This simple adaptation, paired with four curved claws on the other fingers, may have given these small mammals a powerful edge in feeding, processing hard foods, and thriving in diverse environments.

From Claws to a Flat Thumb Nail

Look at your own hands and you’ll notice a familiar pattern: flat nails on most digits, with a broader, flatter thumbnail on the opposing side. For humans, these nails help grip tools and manipulate objects. Researchers studying rodents found a striking parallel: most rodent species possess a flat thumb nail on the first digit (the thumb) and four claws on the other digits. The ancestral rodent likely carried such an arrangement, using the thumb nail to seize and maneuver food while the other digits worked to pry, pull, or hold.

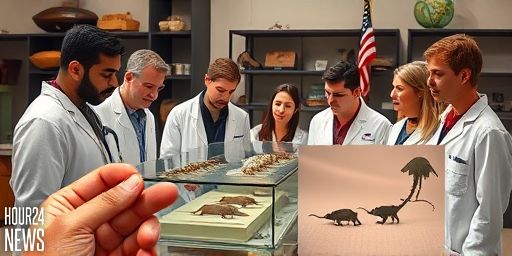

In a study led by a team of mammal researchers, thousands of specimens from the Field Museum’s extensive collection were reviewed. The researchers examined 433 rodent species (out of about 522 described worldwide) to determine not only whether the thumb had a flat nail, but also how different species used their hands to handle food, whether they lived underground, on the surface, or in trees, and what they ate. The project combined museum photos, academic papers, and modern citizen science data from platforms like iNaturalist to reconstruct an evolutionary “family tree” of rodent hand morphology and behavior.

Why the Flat Thumb Nail Matters

The core insight is functional: a flat thumb nail improves grip. When rodents open tough nuts or seeds, they rely on a stable hold while their large, chisel-like incisors do the cracking. In this context, a flat thumbnail acts like a built-in clamp, allowing a rodent to orient, hold, and manipulate food with greater precision than if all digits relied solely on claws or on the mouth. The researchers found that roughly 86% of the studied species retain the classic “one flat thumb nail + four claws” pattern, suggesting strong selective pressure to maintain this configuration across much of the order.

Lineages that Diverged from the Pattern

If the thumb nail provides a grip advantage, why do some rodents diverge from the pattern? Evolution thrives on change, and several lineages show alternative solutions suited to their lifestyles. Burrowing rodents, such as certain spalacids and geomyids (gophers and relatives), sometimes replace the thumb nail with a sturdier claw on the thumb, a modification that facilitates digging through soil. In the Nutallo tree-loving niche, some tree-dwelling species have shortened thumbs with no prominent nail or even absence of the thumb entirely, reflecting a reduced need for grasping in their arboreal niche. Other families, like the Caviidae (guinea pigs, capybaras and their cousins), have largely relinquished the thumb for grazing and gnawing behaviors away from food-handling tasks.

A Simple Feature, Broad Impacts

These anatomical details illuminate why the rodent lineage has proliferated so widely. Nut-cutting efficiency, safe food handling, and the ability to exploit dispersed resources likely contributed to their ecological success. As one co-author noted, the thumb’s nail, discovered across many rodent groups, may explain how these animals so readily exploited high-energy foods like nuts and seeds—resources that can be scarce or contested. The combination of thumb grip and incisor power appears to have created a versatile toolkit for a remarkably diverse order.

Implications for Understanding Mammal Evolution

What begins as a small anatomical cue can cascade into wide-ranging evolutionary consequences. The rodent story underscores how subtle changes in limb morphology can unlock new feeding strategies, influence niche occupancy, and spur diversification over millions of years. The thumb nail may be a simple feature, but its ripple effects help explain why rodents are present on every continent except Antarctica—and why they have persisted as one of the most successful mammalian groups.